From LabHost to Lockdown: Turning 42,000 Phishing Domains into Threat Intel

Hoplon InfoSec

30 Apr, 2025

In a landmark disclosure, the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) published an exhaustive roster of 42,000 domains leveraged by the now-dismantled LabHost phishing-as-a-service (PhaaS) platform. This unprecedented release offers cybersecurity teams around the globe a treasure trove of historical indicators that can sharpen defenses, inform threat-hunting exercises, and guide incident response. By peeling back the curtain on one of the most extensive phishing operations ever observed, the FBI’s report not only chronicles the scale and sophistication of LabHost but also provides a roadmap for defenders seeking to understand and mitigate similar threats in the future.

The Rise and Fall of LabHost

Origins and Business Model

LabHost emerged in November 2021, positioning itself as a turnkey PhaaS solution for cybercriminals. For monthly subscription fees ranging from $179 to $300, its customers—roughly 10,000—gained access to a fully managed suite of phishing tools. LabHost’s operators marketed their platform as an easy, reliable way to spin up fraudulent sites impersonating well-known banks, government portals, postal services, and entertainment platforms. By abstracting away technical complexity, LabHost lowered the barrier to entry for aspiring phishers, effectively industrializing what had once been a more artisanal form of cybercrime.

Scope of Impersonation

Throughout its operation, LabHost catered to deception campaigns targeting more than 200 legitimate organizations. Prominent financial institutions, social media services, e-commerce marketplaces, and even email providers found their brands cloned in meticulously crafted phishing pages. Victims who clicked on malicious links were greeted with near-perfect replicas of login screens, complete with valid SSL certificates and domain names engineered to evade casual detection. The result was a global net that captured credentials, personal data, and one-time authorization codes from millions of unsuspecting users.

Technical Capabilities That Set LabHost Apart

Comprehensive Phishing Infrastructure

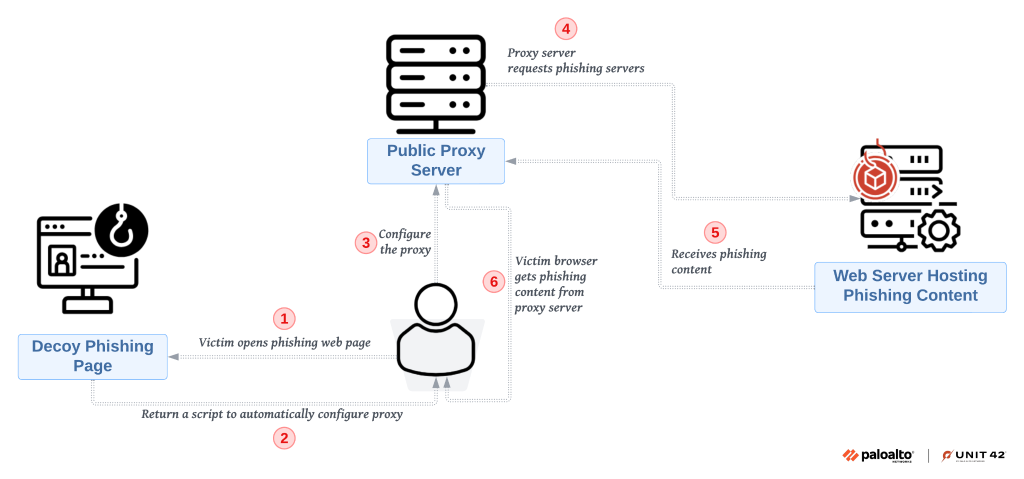

What distinguished LabHost from earlier phishing kits was its end-to-end management console. Subscribers could configure server infrastructure, select templates for phishing pages, and even automate domain registration. This turnkey approach allowed operators to launch new campaigns in minutes. Underpinning the service was a resilient network of proxy servers, load balancers, and automated fail-over routines—architectural decisions mirrored those of legitimate cloud providers, ensuring high uptime and reliability for malicious operators.

Adversary-in-the-Middle Proxying

One of LabHost’s most potent features was its adversary-in-the-middle (AitM) proxy capability. LabHost could transparently the lay authentication challenges—such as multi-factor authentication (MFA) prompts—and capture one-time passcodes in real-time by interposing itself between the victim and genuine real-time This technique effectively neutered the protections offered by two-factor authentication, allowing criminals to log in as the victim moments after credentials were entered. The FBI’s recovery of “LabRat,” the internal dashboard that displayed live sessions and intercepted tokens, underscores just how automated and user-friendly these advanced features had become.

Smishing and Credential Management

In addition to web-based phishing, LabHost integrated SMS-based phishing (smishing) capabilities. Subscribers could upload lists of phone numbers and dispatch customized text messages containing malicious links. Once victims engaged, their credentials flowed into a centralized “vault” along with associated metadata—IP addresses, geolocation data, device fingerprints, and timestamps. These stolen assets were then available for bulk download or direct monetization through fraud-as-a-service resale channels.

The Human Impact: Victims and Financial Loss

Scale of Compromise

According to the FBI, LabHost’s databases held over one million unique user credentials and nearly 500,000 compromised payment card records. The financial damage wrought by these thefts extended far beyond immediate account drains. Stolen credentials fueled fraudulent wire transfers, unauthorized purchases, and money-laundering schemes that moved illicit proceeds through layered financial networks. Many victims faced lengthy disputes with banks and credit agencies, enduring monetary loss and protracted damage to credit reputations.

Demographics of Victimhood

While LabHost targeted victims across all regions, specific campaigns focused on high-value geographies and demographics. Corporate finance and human resources employees were prime targets for business-email-compromise (BEC) style attacks, while retail customers fell prey to credential-harvesting pages impersonating popular online marketplaces. Elderly and less tech-savvy populations proved especially vulnerable, often failing to distinguish authentic communications from malicious clones. Sometimes, victims shared one-time codes with attackers over the phone, unknowingly granting full account access.

International Takedown Operation

Coordinated Law Enforcement Effort

In April 2024, following an 18-month investigation, LabHost was dismantled through a synchronized operation led by Europol in collaboration with the FBI and law enforcement agencies from 19 countries. Seventy search warrants were executed simultaneously across multiple continents, leading to the arrest of 37 individuals suspected of operating or supporting the PhaaS platform. Four principal administrators were apprehended in the United Kingdom, severing the leadership that had kept LabHost running smoothly.

Seizure of Infrastructure and Data

Authorities seized command-and-control servers located in data centers across Europe and North America. Forensic imaging of these servers yielded the full complement of domain registration records, configuration files, and subscriber logs. The FBI extracted the list of 42,000 malicious domains from this trove, along with their creation timestamps and associated metadata. This forensic goldmine facilitated public disclosure and armed law enforcement with evidence for criminal prosecutions and civil injunctions.

Leveraging the Domain List for Defense

Historical Research and Threat Hunting

Although many disclosed domains are no longer active, they represent a historical fingerprint of adversary tactics, techniques, and procedures (TTPs). Security operations centers (SOCs) can ingest this list into SIEM (Security Information and Event Management) tools, threat-intelligence platforms, and intrusion-detection systems to retroactively scan logs for any past connections. Identifying even a single match should trigger immediate user outreach, forensic review of endpoints, and password resets. Analysts can also anticipate how future PhaaS offerings structure their infrastructure by studying the domain naming conventions and registration patterns.

Indicator Sharing and Collaboration

The FBI has made the complete domain list available through its Internet Crime Complaint Center (IC3) portal. Organizations are encouraged to share novel indicators—such as IP addresses, mail-server hostnames, or payload URLs—that emerge during investigations. Cross-industry information-sharing bodies like ISACs (Information Sharing and Analysis Centers) can incorporate these indicators into community feeds, bolstering collective resilience. Rapid, collaborative dissemination of threat data reduces the window of opportunity for attackers. It helps protect smaller organizations that may lack dedicated threat intelligence teams.

Key Takeaways for Cyber Defenders

Embrace a Proactive Mindset

Waiting for alerts from email gateways or endpoint agents is insufficient when facing advanced PhaaS threats. Security teams must proactively hunt for anomalous DNS lookups, monitor suspicious SSL certificate requests, and analyze unusual traffic patterns. Integrating the 42,000‐domain list into regular threat-hunting playbooks transforms passive defenses into active detection campaigns.

Harden MFA Implementations

The adversary-in-the-middle proxying techniques employed by LabHost highlight weaknesses in traditional OTP (one-time password)–-based MFA. Organizations should consider adopting phishing-resistant MFA methods—such as FIDO2 security keys or certificate-based authentication—that are not vulnerable to real-time interception. Regular user training on the dangers of sharing codes and recognizing social-engineering ploys remains a critical complement to technical controls.

Maintain Incident Response Readiness

The speed at which PhaaS operations can spawn new domains and deploy fresh campaigns demands an agile incident response (IR) posture. IR teams should rehearse large-scale credential compromise scenarios, incorporate domain-blocklisting procedures, and establish communication templates for rapid user notification. Partnerships with registrars and hosting providers can expedite takedown requests when fresh domains are detected in the wild.

Conclusion: Turning Intelligence into Action

The FBI’s disclosure of 42,000 LabHost‐associated phishing domains represents more than an academic exercise in historical documentation. It is a clarion call for cybersecurity professionals to convert raw data into actionable defense measures. By studying the tactics that powered one of the most sophisticated PhaaS platforms, defenders can sharpen detection logic, fortify authentication schemes, and tighten incident response processes.

Ultimately, the battle against phishing is an ongoing arms race.

Threat actors will undoubtedly evolve new platforms and techniques. Yet by leveraging shared intelligence—such as the FBI’s domain list—and by fostering international collaboration, the cybersecurity community can raise the cost of attack and protect millions of users from falling victim to tomorrow’s scams. The LabHost takedown is a milestone achievement; the next step is ensuring its lessons translate into stronger, more resilient defenses everywhere.

Share this :