11,000 Downloads and Rising: Villager AI Pen Testing Tool Faces Abuse Concerns

Hoplon InfoSec

15 Sep, 2025

AI Pen Testing Tool Villager PyPI Abuse Concerns

When a little-known package suddenly crosses 11,000 downloads on a public registry, it is not just a number. That spike can reveal an eager security community, curious developers, and, worryingly, bad actors. The story of an AI pen testing tool, Villager PyPI Abuse Concerns, is a modern cautionary tale about openness, power, and responsibility. It asks a simple question: when tools meant to harden systems are easy to pick up, who controls how they are used?

I remember a similar tension years back when automated scanners moved from research labs into wide use. The same pattern repeats: innovation helps defenders, then some people weaponize the same tricks. This piece walks through how the tool works, why the download surge matters, the kind of abuse that worries people, and practical steps defenders and platforms can take.

What is Villager, and why does it matter to security pros?

At its core, Villager is an automated penetration testing utility published as a Python package. For many practitioners, the appeal is simple: a packaged workflow that can probe common weaknesses faster, with less setup, than cobbling together scripts. That kind of convenience accelerates legitimate security testing and lowers the barrier for small teams to evaluate their systems.

Still, convenience has a price. The same ease that helps a junior security analyst can help a novice attacker. The phrase “AI Pen Testing Tool Villager PyPI Abuse Concerns” captures that tension: Villager is a tool that bridges automation and threat research, and when it sits on a public registry, the line between study and misuse blurs. Security teams need to understand both the power and the potential for harm.

Inside the tool: features, mechanics, and how it runs

Villager bundles a set of automated probes, fingerprinting routines, and exploit orchestration scripts into a single package. It aims to identify misconfigurations, weak endpoints, and common software vulnerabilities. The package provides configuration files, runbooks, and sample workflows so users can begin scanning quickly without building a toolchain from scratch.

Under the hood, these features are straightforward pieces of mature tooling: vulnerability scanning engines, credential testers, and payload modules. What makes Villager notable is how these pieces are glued together and how easy it is to run targeted campaigns with minimal setup. That is great for defenders who need a reproducible test plan. It becomes risky when the same workflows are repurposed by people without ethical guardrails.

The PyPI surge: what 11,000 downloads actually means

Numbers attract headlines, and 11,000 downloads looks big. In practice, download counts can come from many sources: individual testers, continuous integration systems fetching packages, mirrors, or automated bots. That means the figure is a signal mixed with noise. Still, the speed and timing of the spike matter. A steady, organic rise tells a different story than a sudden explosion.

When the registry shows a rapid uptick, the community reads it as a potential indicator of either rapid adoption among legitimate users or of mass scanning by malicious actors. In either case, defenders should pay attention. A tool that gets into the hands of many less-skilled attackers can change the threat landscape quickly because it lowers the entry cost for offensive campaigns.

Where abuse concerns come from: dual use explained

“Dual use” is the technical term for tools that have both legitimate and malicious applications. Penetration testing frameworks fall squarely into this category. The core problem is availability: when exploit flows, credential testing routines, and automation are packaged and shared, they become a toolkit for anyone with access.

The worry shared across incident response teams is not theoretical. If a package includes modules that automate credential stuffing, RCE checks, or automated lateral movement proof-of-concept steps, it compresses what used to be a months-long learning curve into a few command lines. That is exactly when the phrase “AI Pen Testing Tool Villager PyPI Abuse Concerns” becomes concrete: the registry amplifies distribution and makes misuse easier.

Real-world misuse scenarios and plausible threat

Imagine a small, opportunistic attacker scanning the internet with a few commands. With Villager or similar packages, they can identify poorly updated web frameworks, guess weak admin passwords, and attempt common exploitation paths at scale. Combined with commodity hosting and stolen credentials, automated toolchains multiply impact.

There are also subtler risks. Attackers can adapt benign-sounding modules into staging tools. A workflow built to identify vulnerable backups could be repurposed to locate and exfiltrate sensitive data. These scenarios underscore the need to treat any broad distribution of offensive functionality with caution and to consider defensive controls beyond simple patching.

Ethical use cases: how red teams and defenders benefit

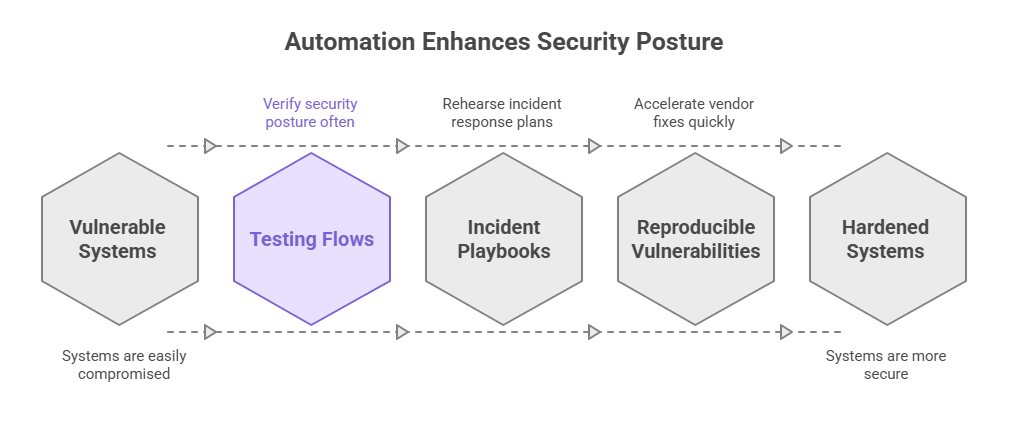

The same automation that worries defenders also equips security teams to harden systems faster. For small companies without dedicated red teams, packaged testing flows mean they can verify security posture more often and catch regressions that manual checks miss. The tool can serve as a rehearsal platform for incident playbooks and a training aid for junior engineers.

There is also a research benefit. When researchers publish tools, they provide reproducible ways to demonstrate new classes of vulnerabilities, which can accelerate vendor fixes. That positive side is important to acknowledge when discussing the phrase “AI Pen Testing Tool Villager PyPI Abuse Concerns.” Not every public package is a threat, but we must manage risk intentionally.

Developer responsibility and open-source stewardship

Maintainers carry a responsibility. Publishing offensive capabilities into a public package without clear restrictions is risky. Practices that help include explicit licensing, clear usage guidelines, rate limiting in default configs, and opt-in destructive modules. Maintainers can also require authentication or vetting to access sensitive features.

Open-source stewardship goes beyond the author. The contributor community, package reviewers, and even downstream users play roles. If maintainers care about reducing misuse, they can add safeguards and monitoring hooks, document ethical use, and work with registries to flag risky behaviors. That constructive approach reduces friction while supporting legitimate work.

PyPI, platform response, and ecosystem safeguards

Registries and platforms can do more than host: they can influence safety. Measures like abuse reporting channels, malware scanning, stricter package metadata requirements, and faster takedown options are practical levers. For packages with known offensive capabilities, a dialog between maintainers and registries helps define acceptable defaults.

Platform teams have to balance openness with risk. Heavy-handed takedowns will drive researchers underground, but lax policies will let harmful tools spread. Ideally, registry policy evolves to support responsible disclosure of offensive tooling and to onboard maintainers into safer publishing workflows.

Community reaction: debate between research and harm

For every defender who warns about misuse, there is a researcher arguing that hiding tools reduces transparency and stifles progress. The debate is not new. It is heated because the stakes are high: research drives fixes, and fixes save users. At the same time, the community cannot ignore real exploitation that follows wide distribution.

That tension fuels practical proposals: publish research but sanitize exploit modules, document limits, and create gated access for risky capabilities. The discussion around the phrase “AI Pen Testing Tool Villager PyPI Abuse Concerns” often centers on where to draw that line.

Legal and policy considerations for tool authors and users

Different jurisdictions have different thresholds for legal risk. Publishing code that automates attacks may raise liability if used for wrongdoing. Authors should consult legal counsel and adopt licenses and terms that clearly prohibit misuse. Users, particularly security professionals, should confirm lawful authorization before running active tests.

Policymakers also need to consider how to treat dual-use software. Criminalizing legitimate research can chill defenders and academics, but allowing unfettered distribution can broaden harm. Lawmakers, platform operators, and the security community must coordinate nuanced policies that protect both research and the public.

What organizations should change in practice now?

Organizations should assume tools like Villager exist and plan accordingly. That starts with basic hygiene: patching, strong authentication, and monitoring. Beyond that, teams should conduct regular, authorized red team exercises and harden high-value targets before attackers exploit easy wins.

Investing in detection is vital. Logging, anomaly detection for login attempts, and multi-factor authentication reduce the impact of automated credential stuffing. The organizations that respond quickly are those that treat distribution of offensive tooling as an expected change in the threat landscape.

Detecting misuse and practical incident response tips

Practical detection begins with telemetry. Unusual scanning patterns, repeated failed authentications, and bursts of suspicious activity often precede compromise. Teams should tune alerts for rapid spikes and prioritize triage for exposed services.

If misuse is detected, follow a standard incident response playbook: contain, analyze, eradicate, and recover. Document the attack vectors, update detection signatures, and share indicators with relevant communities. Transparent reporting can help the ecosystem respond faster to emerging abuse patterns.

Alternatives, safer tooling, and building responsibly

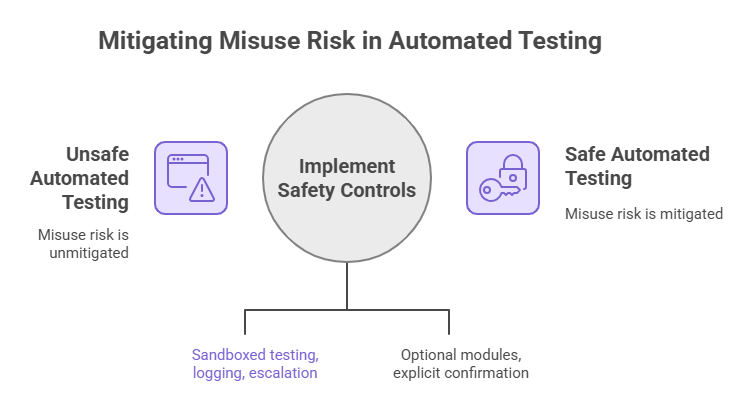

Organizations that need automated testing should consider managed platforms that provide the same function with safety controls. Gatekeepers such as enterprise offerings or vetted vendors can provide sandboxed testing, logging, and escalation features that mitigate misuse risk.

For open-source authors, safer design patterns matter. Make destructive modules optional, require explicit confirmation for dangerous operations, and provide default rate limits. Those small design choices make a big difference when tools are shared on public registries.

Final takeaway and actionable recommendations

The rise of an AI pen testing tool, Villager PyPI Abuse Concerns, is not a simple binary of good or bad. It is a mirror showing how openness and power interact. Packages that help defenders can also help attackers if safeguards are missing. The responsible path is not to hide research but to publish with care.

Actionable steps are clear. Maintain good hygiene, invest in detection, push maintainers and registries to adopt safer defaults, and demand transparent practices from tool authors. If you are a maintainer, document ethical use, add safeguards, and engage with the platform. If you run a network, assume automated toolkits exist and harden accordingly.

One last thought. Tools will continue to become easier to use. That is progress. The question is whether the community will pair that progress with the discipline to limit harm. If we do that, the same tools that once raised alarm can become the instruments we use to prove systems are safe.

With tools like Villager AI Pen Testing Tool circulating, organizations face real risks. Hoplon Infosec’s Penetration Testing offers a safe, professional way to identify vulnerabilities, simulate attacks, and secure systems before they can be exploited.

Follow us on X (Twitter) and LinkedIn for more cybersecurity news and updates. Stay connected on YouTube, Facebook, and Instagram as well. At Hoplon Infosec, we’re committed to securing your digital world.

Share this :