Dynamic DNS Attacks: How Hackers Exploit DDNS Services to Hide and Strike

Hoplon InfoSec

29 Sep, 2025

Your ISP gives you a new IP address every time your router restarts if you have a small server or webcam at home. Even though your IP address has changed, you want people to be able to get to "myhome.example.com." Dynamic DNS makes sure that your domain name always points to the right IP address. It's useful and easy to use, but there are also some risks that not many people think about.

Attackers have figured out how to use dynamic DNS to their advantage because it lets DNS records change on the fly. They can hide their malicious infrastructure behind it, switch servers, get around blacklists, and make command and control channels that are hard to break.

In recent years, security researchers have observed that advanced threat groups increasingly rely on dynamic DNS attacks to hide command-and-control infrastructure and evade detection (CISA, 2023; FireEye, 2022).

This article talks about how threat actors are using dynamic DNS providers, why defenders have a hard time keeping up, and what you can do to stop them.

What does DDNS stand for?

Dynamic DNS, or DDNS for short, is a service that changes the DNS records for a domain name automatically when the IP address changes. It fills in the gap between an IP address that changes and a domain name that stays the same. A lot of small businesses, hobbyists, remote workers, and IoT devices use it to keep access without having to change DNS settings by hand.

DDNS is like a "live update" system, while regular DNS keeps an IP address pretty much the same. When your router or computer sees that its outward IP has changed, it sends a signal to the DDNS provider to update the DNS records to the new address. Even if your ISP changes your address, people can still find you by typing "myname.ddns.net."

DDNS is often easier to use and more flexible, so it doesn't always have as many checks. For instance, it might have fewer registration requirements, a less strict verification process, or even anonymous subdomain hosting. That ability to change is what makes it so easy for hackers to get in.

How Dynamic DNS Works Behind the Scenes

When a host's IP address changes, a small agent or script sends an update to the DDNS provider's API or update endpoint. The provider then updates the zone file so that the DNS record for the domain points to the new IP address. That happens really fast.

The DNS system sends traffic with this domain name to the current IP address from the user's end. The DNS resolver cache and TTL (time to live) values might slow down propagation a little, but updates happen quickly for short TTLs.

Some providers let people rent subdomains that are part of a shared root domain. For example, yourname.some-ddns.com. Some of them let you use your own domain, but they still take care of updates that happen automatically. The service usually works with more than one type of record, such as A, CNAME, and others. Sometimes it has more advanced features.

This mechanism is safe by itself. But because the update path is automatic and often not very secure (or not at all secure in older systems), bad people have found ways to get in with little trouble.

Why hackers like dynamic DNS

There are a lot of reasons why bad people like to use dynamic DNS to do bad things:

• Easy to sign up. You can sign up for many DDNS services without having to prove your identity, and some even let you do it with anonymous email or cryptocurrency payments.

• Getting past IP blocking. Static blocking of known bad IPs isn't as effective because the IP address behind a domain can change at any time.

• Being able to deal with stress when being taken down. Attackers can quickly switch to a new server by updating DNS records if one of them goes down or is blacklisted. The domain stays up.

• Making it hard to see the infrastructure. It's harder to find out who did the attack and where they are because the attack infrastructure isn't linked to just one IP address.

• Hide subdomains. Using rented subdomains under well-known root domains makes links that are bad look less suspicious.

In short, dynamic DNS gives attackers speed, stealth, and flexibility things that defenders have to work hard to stop in real time.

Common Dynamic DNS Attack Patterns

Attackers don't usually come up with new ways to attack; instead, they change old ones by using DDNS as a base. Here are some common patterns:

• Changing C2 based on DNS. The malware connects to a domain whose DNS record might change with each hop.

• A fast-flux-style rotation. A domain points to many IPs that change all the time.

• Infrastructure for phishing. Attackers put phishing pages on dynamic domains that change to avoid getting shut down.

• Servers that host or drop malware. The payload comes from a dynamic hostname that changes, so it can't be blocked.

• Proxying or tunneling. By putting proxies behind a dynamic domain, attackers can hide real endpoints.

One security blog says that "DDNS services are often used to enable other attacks like phishing, fast-flux, or malware command and control."

Strategies for fast-flux, double-flux, and dynamic resolution

You may have heard of "fast flux" networks in relation to botnets. In single-flux mode, a domain changes its IP address quickly, maybe every few seconds or minutes. In double-flux, both the IPs behind the domain and the names of the DNS servers (name servers) change. This makes things even harder.

The MITRE ATT&CK framework includes dynamic resolution techniques as Technique T1568. This is what hackers do to avoid being caught: they change their domain names, IP addresses, or ports on the fly.

These changing tactics make the standard approach weak because defenders often whitelist domains or IPs in a way that doesn't change. The domain might have moved to a different IP address by the time you block it.

Renting Services for Subdomains and Platforms That Can Be Misused

One of the newer tricks is to rent subdomains from a root domain that a DDNS provider owns. Hackers rent a subdomain, like bad.sub.dyndnsprovider.com, instead of buying a whole domain. From the outside, it looks like a real address under that root. Because the root is "trusted," the subdomain looks more real.

Scattered Spiders and other groups have used this trick to make people think they are well-known brands in phishing campaigns. Dark Reading These subdomains look more "normal" than new domains with strange TLDs that don't seem to fit in anywhere.

Some DDNS providers don't pay close attention to things. They don't do strict KYC checks, and they don't do much to stop people from abusing the system. That's why people who do dynamic DNS attacks like them so much.

Threat actors and groups that have used DDNS in the past (case studies)

Dynamic DNS attacks are now part of the toolkit of real threat groups. Here are a few examples:

• Scattered Spider is a group that steals information through phishing and social engineering.

They have rented subdomains from DDNS providers to make their fake brands look more real.

• APT28/Fancy Bear has been connected to DDNS domain infrastructure in the past.

• Reports say that APT29 used dynamic DNS domains in their QUIETEXIT C2 communications as part of their campaign work.

• Some groups that use dynamic DNS infrastructure in their work are Gamaredon, APT10, and APT33.

These examples show that dynamic DNS attacks can help both criminals and government workers. They aren't just tools on the edge.

Dynamic DNS in the Command and Control (C2) System

One of the most strategic ways that attackers use dynamic DNS is to build command and control (C2) channels. When malware gets into a computer, it "calls home" to a domain. It could point to a control server whose IP address changes when necessary.

If the domain isn't linked to a specific IP address, attackers can move around freely. If one server is flagged, they can just change the domain's address. It is harder to defend because it can change.

Sometimes dynamic DNS can get through because not all firewalls check DNS traffic closely (most firewalls let DNS lookups through by default). This channel can be a secret control line for hundreds or thousands of infected nodes when used with encryption or tunneling.

Attackers might also preload a lot of subdomains or different versions of a domain and turn them on as backups if the main ones are blocked. That way, they keep going even when things get hard.

DDNS can hide malware, phishing, and infrastructure.

Dynamic DNS attacks affect more than just C2 infrastructure. Attackers also use DDNS to host malware, hide their infrastructure, and send phishing emails.

Changing the domains used for phishing makes it much harder for defenders or registrars to take them down quickly. A domain could host the fake login page for hours, then go away and come back somewhere else.

For malware hosting, the payload or exploit kit may be hidden behind a hostname that changes. Once defenders block that hostname, attackers can just point it to a different place.

Attackers might use DDNS-hosted proxies to hide real back ends because dynamic DNS lets them use hacked routers or IoT devices as endpoints. This adds more hops and makes it hard to find the real server.

Problems with DNS Dynamic Updates and Zone Hijacking

Attackers use weak dynamic update mechanisms in DNS itself and DDNS as infrastructure. Some DNS zones let dynamic updates happen without being secure, so they don't have to be verified. A study that came out recently looked at 353 million domain names and found that about 381,965 of them accepted DNS updates without asking. This is a big possible way for an attack to happen.

If an attacker can take over the zone this way, they can poison it by adding, deleting, or changing records. They could change the flow of traffic, add bad subdomains, or take complete control of the domain.

When DDNS is used with TLS that isn't set up right or appliances (like routers or QNAP devices) that aren't safe, it can also make it easier to find or see internal devices.

To sum up, there are some problems with how dynamic DNS is used and set up.

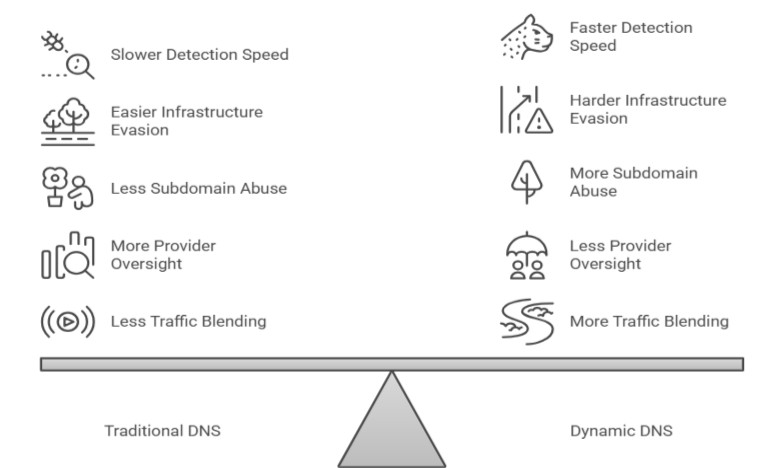

Detection Problems: Why It Gets Through Defenses

Here are a few reasons why dynamic DNS attacks are hard to find:

• How quickly it turns. IP addresses change too quickly for static blocklists to keep up.

• Not very suspicious at first. DDNS is used by a lot of real services, so the traffic patterns look normal.

• The subdomain is not clear. Heuristic filters don't catch bad subdomains that are under real root domains.

• Mixing up traffic. Attackers often use DNS to hide bad traffic or protocols that mix in with normal traffic.

• Not being able to see. Many security tools don't pay much attention to changes in DNS records over time or their history.

So, defenders might only see pictures of bad domains and not the changes that show a dynamic DNS attack is going on.

Best Ways to Protect Yourself and Best Practices

Dynamic DNS attacks are hard to do, but there are ways to keep yourself safe:

1. Keeping an eye on DNS and looking for strange behavior. Watch out for domains whose IPs change too often or that move around a lot.

2. Threat intelligence feeds. Sign up for lists of known bad DDNS domains that are updated often and block them ahead of time.

3. DNSSEC and updates that have been checked. To stop changes from happening without permission, use secure DNS updates and signing.

4. Set a limit on how often updates can happen. Restrict the hosts or systems that can change dynamic DNS and require strong authentication.

5. Controls for limiting the rate and time to live (TTL). Don't let very low TTLs make it easy to change quickly.

6. Checking or filtering subdomains. Be careful with subdomains that are part of DDNS root domains that aren't very well known.

7. Learning about behavior. Instead of paying attention to static indicators, pay more attention to behaviors that seem strange, like DNS churn that happens a lot or traffic that is out of the ordinary.

8. Working with providers. Contact DDNS or DNS providers right away to report abuse.

These strategies won't stop all abuse, but they will make it much more expensive for attackers.

Collaboration among DNS providers, researchers, and law enforcement

A big part of this puzzle is working together. DDNS providers need to make it easier to check, find problems, and report abuse. Security researchers should share information about bad dynamic DNS domains, and police should quickly take down infrastructure in the meantime.

There are some success stories: when CSIRTs (Computer Security Incident Response Teams) were told about dynamic update domains that weren't safe, many were able to fix the problem.

The main problem is that many DDNS providers operate in areas where there isn't much regulatory oversight.

It might be possible to change the balance by making the system of accountability stronger and sharing abuse signals in real time.

Future trends and strategies for dynamic DNS attacks that are changing

I see these trends happening in the future:

• More automated chaining: using AI or scripts to make new dynamic domains quickly.

• Hybrid models that use DDNS with bulletproof hosting or networks that keep you anonymous.

• Using domain generation algorithms (DGAs) with DDNS more often to hide command and control.

• More mixing of good and bad services: using cloud providers, IoT endpoints, or trusted infrastructure to hide abuse.

• Maybe new rules or protections at the DNS protocol level to make it easier to find and stop dynamic abuse.

Attackers are always looking for new ways to break in. We also need to make our defenses stronger.

Things You Can Do

Dynamic DNS is a great tool, but hackers really want to get their hands on it. Dynamic DNS attacks give enemies speed, stealth, and power. Traditional defenses have a hard time with it because it changes all the time.

Remember these three things:

1. Remember DNS. Watch it closely, see how it changes, and act like it's a very secure area.

2. Set limits on dynamic permissions. Only let trusted agents change DNS, and make them show proof of who they are.

3. Give out information quickly. Get help from DDNS providers, security groups, and the police to find and stop abuse.

In a world where IPs and subdomains are always changing, the best ways to protect yourself from dynamic DNS attacks are to stay alert, work together, and be ready to change your defenses. I can also help you make blog posts, slides, or pictures out of this if you want.

Dynamic DNS attacks are a growing challenge CISA warns that attackers use these services for resilient command-and-control, while Gartner highlights DNS-layer protection as a key defense against evolving threats.

Hoplon Insight Box:

Monitor dynamic DNS updates.

Use DNS threat intelligence.

Restrict dynamic permissions.

Report abuse with providers.

Dynamic DNS attacks often target endpoints through hidden connections. Hoplon Infosec’s Endpoint Security service detects and blocks these threats, keeping your systems safe and resilient.

Share this :