Google Infrastructure Domain Fronting Attack: How Hackers Use Meet, YouTube, Chrome and GCP to Evade Detection

Hoplon InfoSec

25 Sep, 2025

Google Infrastructure Domain Fronting Attack

Well-known websites on the internet rarely serve as gateways for illicit activities. Network engineers have been making rules for years based on the idea that services like Google Meet, YouTube, and Chrome updates were off-limits. They were safe, needed, and always on the whitelist. But a new group of attackers has changed that trust.

People are calling this new type of cyber threat “Google infrastructure domain fronting.” At first, it sounds like a lot of technical jargon. But in practice, it’s a way to get bad traffic through the gates that defenders left open on purpose. When I first read the reports, I stopped to think about how smart it was that Google could use its own infrastructure in such a bad way.

What is domain fronting?

Let’s take a step back for a moment to understand this. Domain fronting isn’t a new thing. In the past, hackers and even activists have used it to hide where traffic is really going. It’s like putting a letter in the mail with one address on the envelope and another address on the letter itself. The postal worker delivers it based on what it looks like on the outside, not knowing where it’s really going.

In this new version, attackers break the rules of routing and encryption. They start a normal handshake with a Google service, which makes the network think it’s going to Meet or YouTube. But the real message is hidden inside that handshake. That is the main idea behind Google infrastructure domain fronting. It works because companies don’t often block traffic to Google.

Why Google Services Were the Best Targets

Many businesses around the world depend on Google products. Employees need to make video calls, browsers need to be updated, and cloud apps need to talk to Google servers all the time. Blocking them would make normal business impossible. Because of this reliance, Google services are a great place to hide bad tunnels.

Picture it like a busy train station. With so many people traveling every day, it’s simple for one suspicious person to fit in. Attackers know that sending traffic to YouTube or Chrome update servers won’t raise many eyebrows. They can hide their bad channels in this traffic, which makes them almost invisible.

How the New Attack Gets Past the Security

When malware gets on a victim’s device, the attack chain usually starts. The malware doesn’t call home directly to a suspicious server. Instead, it connects to a Google domain. From the outside, it seems real. But once the encrypted session is set up, the traffic is sent to the attacker’s server through hidden headers.

This move makes it almost impossible for regular defenses to tell the difference between good and bad. Firewalls can see Google, which is on the list of safe sites. Intrusion detection tools look for unknown destinations, not ones that are already on a whitelist. The trick works because there is a difference between what you can see on the surface and what you can’t see on the inside.

What Google Meet did in the attack chain

People use Google Meet for virtual meetings all the time. Companies don’t often question traffic that goes there. Now, attackers take advantage of that trust. They can make their bad messages look like normal Meet traffic by putting them in a package. The suspicious packets get through because IT teams use them every day.

It’s not that Google Meet is dangerous; it’s that attackers use its reputation to their advantage. They cover their tunnels with the well-known handshake of video conferencing, which makes it hard for defenders to see the secret payload moving beneath the surface.

YouTube traffic used to hide undesirable data

YouTube is another smart cover. It gets a lot of traffic all the time and from a lot of different places. Most monitoring tools can’t fully understand the huge amounts of data that come from videos, ads, comments, and live streams. An attacker can send small, regular packets into that storm, and they will look just like regular video requests.

Picture yourself on a beach trying to find one strange wave in an ocean that goes on forever. That’s what defenders have to deal with when bad tunnels are hidden in YouTube traffic. In this kind of noisy setting, Google infrastructure domain fronting does very well.

Chrome Update Servers Used in Secret

Browser updates are one of the most common things. They happen in the background without users even knowing it. Attackers take advantage of this by sending their tunnels to Chrome’s update servers. IT departments need those updates to keep their systems safe, so they can’t block them.

This feature makes the update channel the perfect cover. Updates are supposed to look random, so a connection that lasts longer than expected or sends packets that aren’t the right shape doesn’t set off alarms. Once again, the attacker gets away with it.

Google Cloud Platform’s Hidden Tunnels

The cloud is also a weak point. Many businesses depend on Google Cloud Platform. Traffic there is complicated, with a lot of APIs and background noise. Attackers take advantage of that complexity by putting their tunnels into GCP traffic.

They make paths that defenders often miss by doing this. Among the thousands of real requests that happen every second, an unusual call to a cloud API doesn’t stand out. That’s why Google infrastructure domain fronting is such a pain for companies that rely heavily on the cloud.

Why it’s hard for traditional defenses to see it

Security tools were made a long time ago. They check for IP addresses, domain names, or signatures of threats that are already known. But when the traffic goes to Google, none of those alarms go off. Companies basically told their defenses, “Don’t worry about this lane; it’s safe.”

Attackers rely on that kind of blind trust. Defenders will never be able to see the hidden routing unless they have advanced inspection tools that can look inside encrypted sessions. The attack works because defenders are following rules based on trust, not because they are lazy.

Real Events That Made People Warn

Researchers have already seen this trick in real life. There were reports of attackers hiding their command channels in Meet and YouTube streams. Security teams were confused until they saw the hidden host headers in the packet captures that pointed to other places.

These real-world results made analysts raise the alarm. The message is clear: if your logs only go to the outer layer, you might already be missing tunnels that look fine from the outside.

How attackers make and keep the tunnel

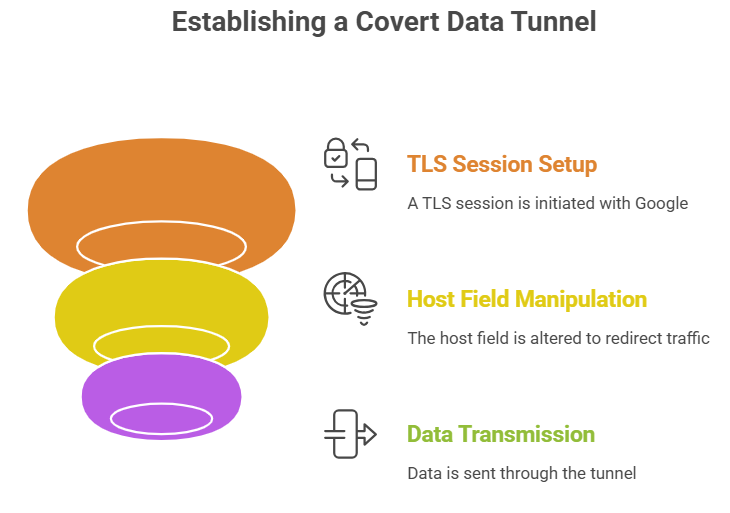

Once the malware is in place, the process is pretty simple from a technical point of view. A TLS session is set up between the client machine and a Google endpoint. The handshake and the outer certificate are both acceptable. But inside the encrypted payload, a different host field sends traffic to the attacker’s server.

After that, the tunnel can stay open for hours. Data goes back and forth while mixing in with real traffic. It’s like having a hidden door in a busy hallway. Attackers like Google infrastructure domain fronting because it doesn’t need any special tools; all they need to do is use existing standards in a clever way.

What Defenders Should Look for in Network Logs

The good news is that there are signs if you know where to look. Unusually long TLS sessions that are trying to connect to Google services could be a sign. A machine that doesn’t use Meet very often but suddenly starts streaming a lot of traffic might be worth looking into.

Even small problems, like packets that are the same size over and over or strange intervals, can show where a tunnel is. Heuristics are now part of advanced monitoring solutions that can find these kinds of patterns, but they need to be set up and adjusted, which takes time.

Quick fixes and quick containment

There are some things companies can do right away if they feel exposed. Make your outbound rules stricter. Don’t just let “all Google traffic” through. Instead, say exactly what endpoints your business needs. Add proxies that can decrypt and look at headers, but this may slow things down.

Even short-term restrictions can make it harder for attackers to keep their secret channels open. If the environment is strict about which Google services are needed, Google infrastructure domain fronting doesn’t work as well.

Mitigation that focuses on the cloud and Google’s own role

Defenders can use Google’s own tools to fight back in the cloud. Companies can limit how their internal systems use Google APIs with features like VPC Service Controls and IAM policies. When you turn on detailed logging of API calls, it’s easier to find patterns that don’t make sense.

There has also been pressure on Google to change its infrastructure to make fronting less likely. While it may not be possible to get rid of everything, being open and working with defenders can help fill in some gaps.

Last Thoughts and Lessons

The emergence of this method demonstrates that even reputable platforms can become weapons. You can’t just trust people blindly anymore. Businesses need to rethink how they define “safe” traffic.

Google infrastructure domain fronting isn’t about Google being bad; it’s about hackers taking advantage of people’s trust. It’s easy to understand but hard to do: treat every channel, even the most trusted ones, as a possible attack path. The companies that change will be the best prepared for the next wave of hidden tunnels.

Share this :