HybridPetya ransomware: How CVE-2024-7344 bypasses UEFI Secure Boot and what to do

Hoplon InfoSec

20 Sep, 2025

HybridPetya ransomware

A short, sharp hook to start: a strain that uses Petya-style encryption and adds a trick that keeps it going at the firmware level sounds like something out of a thriller. This one is real enough to make IT teams stop and double-check their rules for updating firmware. Researchers have said that HybridPetya ransomware is a mix of bootkit and ransomware that can affect the pre-boot layer and the file system in ways that make it hard to recover.

I’ll explain what it is, why CVE-2024-7344 is important, and what smart defenders can do right now. This is not doom porn; the tone here is practical and human. It tells you to think of firmware as part of your attack surface instead of a mysterious black box.

A call to action for firmware security

This episode shows that firmware is not someone else’s problem. Threats that are new are getting lower on the stack. Attackers who can run code before the operating system has a chance to stop them can cause problems that last longer than a simple OS reinstall.

That means that even the best endpoint protection won’t work if the boot chain itself is broken. This is not just a theory. The fact that the new samples have a boot-level capability shows that hackers are now trying things at every level.

What this new strain does

At a high level, it brings together two scary abilities. One way is to put a bad EFI app in the EFI System Partition so that it runs when the computer starts up. Second, it has a destructive phase for the file system that targets metadata instead of just files like classic crypto. That means both persistence and damage to operations.

Researchers recorded how the sample family’s uploads and behavior show that they are using a Petya-style MFT encryption routine with boot persistence. Because the boot code can reinstall or re-trigger destructive actions after an OS reinstall, that combination makes detection and recovery harder.

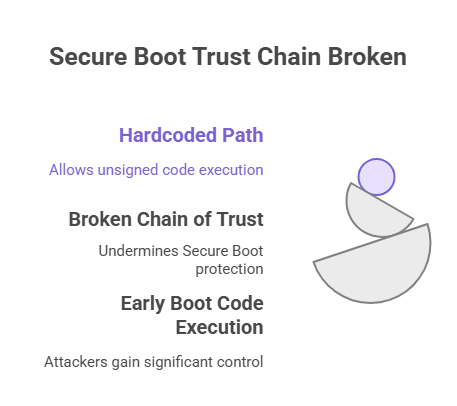

CVE-2024-7344: the weak point

The main part of the story is CVE-2024-7344. Some UEFI apps have a flaw that lets them run unsigned software from a hardcoded path. A signed UEFI component that acts that way breaks the chain of trust that Secure Boot is supposed to protect.

That’s why the name is important. Vulnerabilities that let unsigned code run early in boot are more dangerous than kernel-level bugs. They let an attacker put code that runs before the OS, which gives the attacker a lot more freedom.

What UEFI Secure Boot is and what it protects

Secure Boot is meant to stop untrusted code from running when the computer starts up. The firmware only runs things with the right signatures, and the operating system bootloader checks the kernel, and so on.

That chain falls apart when a signed part acts badly or lets unsigned payloads through. In short, a single signed tool that is vulnerable or not set up correctly can break the safety net that used to stop bootkits.

The EFI System Partition and how hackers use it to their advantage

The EFI System Partition (ESP) is a small, often ignored partition that holds real boot files. It’s also a good place for attackers to leave a persistent component because the firmware will look at those files when the computer starts up.

The new samples were found to install an EFI application to that partition, which means that the malicious part can run every time the computer starts up. That is a foothold at the firmware level, and it is one reason why defenders need to check the ESP when strange boot behavior or repeated infections happen.

What Master File Table encryption is and how it stops recovery

This type of malware not only encrypts individual files, but it also attacks the Master File Table of NTFS. The MFT has information about every file, so if it gets messed up, operating systems have a hard time finding or getting to data, even if the raw file content is still there.

That design makes normal file-level recovery tools work less well. When you restore data, it’s more about forensic recovery and backups than just running a decryptor.

Copycat or real evolution: linking Petya, NotPetya, and now this

The way disk and metadata parts are targeted is similar to Petya and NotPetya. But adding a UEFI foothold is a step up. It would be easy to call it a copycat, but the fact that the firmware stays the same shows that attackers are learning: they often build on old ideas and add new ones.

Histories like this show how enemies use old harmful ideas and new low-level techniques to their advantage. A lot of researchers are using that hybrid approach to name this family.

Who is in danger, and where do defenses usually break down?

Organizations that use third-party recovery tools, older firmware, and machines where Secure Boot signing options are widely available are in the at-risk group. Systems that haven’t installed vendor firmware updates or that still have third-party signing turned on are more vulnerable.

Another operational failure point is that teams don’t check the ESP often enough and don’t have automated monitoring of boot entries very often. That’s where persistence hides in the gap in visibility.

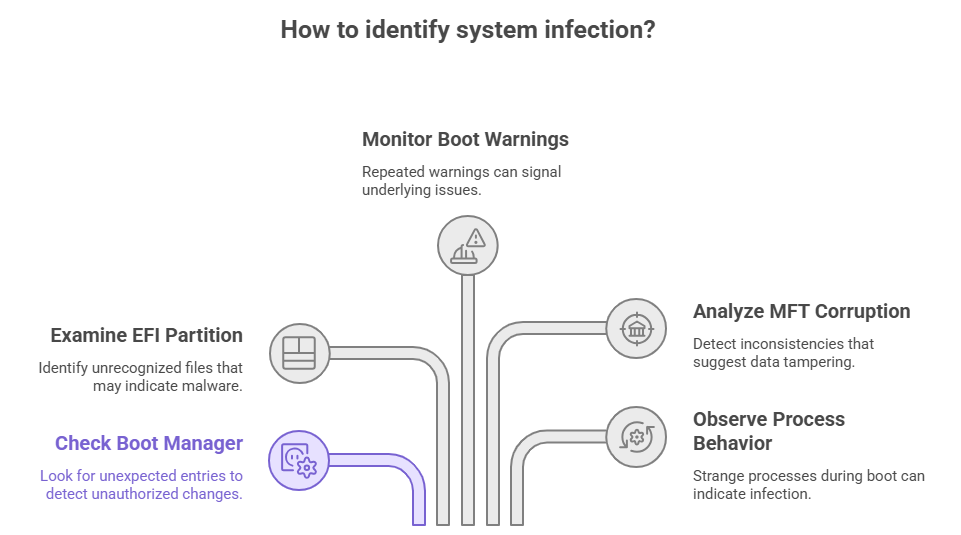

How to find the infection: signs and IOCs

Check the system boot manager for new entries that you didn’t expect, the EFI partition for files that you don’t recognize, boot-time warnings that happen over and over, and signs that the MFT is corrupted. On the host side, strange process behavior during boot and tools that find differences between file listings and file content are big red flags.

In the end, threat intel feeds will share IOCs, YARA rules, and SIEM queries. Until then, hunting should focus on the ESP, the boot configuration, and strange MFT changes that happen out of the blue.

Immediate containment: the first 12-hour plan

If you think a machine is infected, cut it off from the network right away and keep the disk image for forensic analysis. Don’t just re-image; if the firmware is damaged, reinstalling the OS may not get rid of the persistence. Keep the EFI partition and make a copy of it for later use.

Talk to stakeholders, get volatile logs, and add any trending indicators to your detection tools. Also look at telemetry to see if there are any similar signs in other assets.

Cleaning the firmware layer: steps to fix things for the long term

For a firmware-level compromise, you may need vendor firmware updates, UEFI revocation lists, and sometimes a clean firmware re-flash. Earlier this year, vendors revoked affected signed binaries and released patches, so it’s important to follow those contracts and vendor advice.

Also, if you can, turn off unnecessary third-party UEFI signing and lock down boot options in the firmware settings. Make sure that your secure boot db and dbx revocation lists are up to date, as well as your list of firmware components.

Backups, recovery, and the false belief that reinstalling always works

A simple reinstall of the operating system won’t fix the problem if the firmware is still there. The cycle keeps going until the boot-level component is removed or made useless if a malicious EFI component can reintroduce a payload after reinstalling.

The lesson is to make sure you have backups that can’t be changed and to plan for recovery that includes checking the firmware and cleaning the hardware when necessary. Before bringing systems back online, restores must check that the boot is working properly.

Questions about procurement, vendors, and the cleanliness of the supply chain

Buyers should ask vendors if their recovery tools work with UEFI, if they use third-party signing, and how the vendor handles vulnerabilities that are found. The language in the contract should require quick fixes and communication of revocation events.

A procurement policy that looks for safe development practices and quick patching can lower risk. Also, make sure that your operations team can always follow clear instructions for updating firmware.

Things you should remember from past bootkit problems

We learned from past attacks that firmware attacks are sneaky and hard to stop. The BlackLotus case and others like it taught the industry that revocation lists and working together with vendors work, but they take time.

The lessons learned are the same: keep your firmware up to date, limit third-party signing, keep forensic images, and think of the pre-boot environment as part of your security perimeter.

A list of things to do and some final thoughts

A short list of things to do today: check the versions of the firmware, make sure the Secure Boot settings are correct, update the vendor firmware, keep an eye on the EFI partition, check the offline backups, and make plans for firmware validation during recovery. These steps are practical and doable.

HybridPetya ransomware is a reminder that hackers are using both long-lasting and destructive payloads. The technical details are important, but so are the human ones. Training, checklists, and a calm, practiced incident plan will do more to protect you than panic. You will sleep better if you treat firmware like any other important layer.

HybridPetya ransomware proves that attackers are targeting the very core of systems. Hoplon Infosec’s Endpoint Security services help detect, block, and respond to threats at this critical layer, keeping your business resilient against even the most advanced attacks.

Share this :