Multi-Stage Windows Malware Disables Defender Before Payload Attack

Hoplon InfoSec

22 Jan, 2026

What exactly is this multi-stage Windows malware that can turn off core Windows security protections and then infect systems with dangerous code? In simple terms this new threat is a complex, layered attack that first shuts down Windows Defender, disables Defender protections, and then quietly delivers harmful software that can steal data, take control of machines, or encrypt files for ransom. Digital risk professionals and everyday users alike should understand how it works and how to respond.

How This Multi-Stage Attack Begins

When you hear about a Defender bypass malware attack in recent reports, it generally means bad actors are using multiple steps to get inside a Windows device without getting caught. Instead of trying a single trick, this multi-stage Windows malware campaign uses a sequence of techniques to achieve full system compromise. Smart attackers often start with something that looks safe to the user, like a socially engineered document or a legitimate‑looking download link, to lure someone into opening it. Once clicked, the first component runs quietly and begins mapping out the environment.

In the earliest phase the attackers obtain some level of access that lets them run code on a user’s machine. This might come from a phishing email, a compromised website file, or even something that seems normal to the casual eye. At this point defenders are watching for obvious malware, but well‑crafted staging sequences can evade basic scanners and raise no immediate alerts. The first payload sits and waits until it is ready to escalate the attack.

Disabling Microsoft Defender and Other Protections

One of the most concerning behaviors in this attack chain is how the malware neutralizes built‑in Windows protections. Modern versions of Windows include Microsoft Defender to block malicious files and suspicious activity. But these attackers misuse tools like Defendnot or registry manipulation to trick the system into believing its security software has been replaced or is no longer needed. When Windows thinks another antivirus is present, it willingly stops Defender to avoid a conflict.

This isn’t a one‑off fluke. Multiple analyses show that threat actors are turning legitimate system management interfaces into attack surfaces. By registering dummy software or abusing undocumented Application Programming Interfaces (APIs) in the Windows Security Center, the malware effectively tells Windows to stop Defender. Once Defender is off, the usual real‑time threat blocking and behavioral protection are gone.

One researcher explained that Windows disables Defender automatically when it detects what it thinks is a trusted third‑party endpoint protection service on the system. This design decision makes sense for performance and conflict reduction. But attackers now use that logic to their advantage.

The Role of PowerShell and Scripted Execution

In many modern threats you will find PowerShell malware execution listed as a step. PowerShell is a powerful scripting environment built into Windows that administrators use for automation. Unfortunately that power also makes it attractive for attackers to hide their actions. Because PowerShell can be used without writing files to disk, it is harder for traditional defenses to spot.

Once Defender is disabled, the malware often starts using PowerShell scripts to download and execute additional tools. These scripts might pull down payloads from cloud services or attacker servers, even if the files are encrypted or obfuscated. In a multi‑stage infection chain Windows malware often uses this central scripting language as the glue between each phase of its activity.

Stages of the Attack and Payload Delivery

So what happens after the security tools are turned off? This is where the attack pivot moves into what many defenders fear most. With Defender offline, the attackers can deploy a range of harmful components. In some cases this includes a remote access trojan that lets the intruder see everything on the machine. In other cases encrypted ransomware payloads are dropped and triggered.

Experts have documented cases where the resolved attack chain progresses like this:

• Initial social engineering lure delivered via email or document.

• The first-stage downloader runs, largely invisible to endpoint protection.

• Defender and other protections are neutralized or hidden using spoofed registration or API abuse.

• A second‑stage payload connects to remote servers to fetch advanced tools.

• Final payloads are executed, which may include surveillance tools, encryption engines, or data exfiltration modules.

This layered approach is purposeful. Each part of the toolchain has a role to play, and none of the components need to be overtly malicious on their own. Only in sequence do they create a full breach.

Why These Attacks Work So Well

When this kind of Windows malware disables Defender services and other protections, the usual safety nets for users and organizations fail. That means basic antivirus signatures, heuristic alarms, and even some endpoint detection tools may not see the threat until it is too late. Cybercriminals have learned to weaponize native Windows functionality against itself.

In addition, the modular strategy lets attackers update or rotate parts of the chain without changing everything. For defenders this creates a moving target that is harder to detect using simple signature‑based approaches. As documented in recent threat research, attackers may host screening scripts across public cloud services and rotate payload locations to avoid takedowns, which further complicates detection and tracking.

This is part of why advanced EDR solutions and more detailed malware threat analysis are necessary. When Defender and similar protections are intentionally sabotaged, only tools that can log actions deeply and spot anomalies across systems have a chance at early detection.

Real-World Impact on People and Businesses

For everyday users, this kind of attack can feel invisible. You might click what seems like an ordinary file, and suddenly your system is compromised without any obvious warning. A personal anecdote from a small business owner illustrates this risk well. They reported that emails arrived looking like routine invoice updates from a trusted partner. After opening the attachment, Defender suddenly showed it was off, and scans stopped running. Within hours, documents were encrypted, and the attackers demanded payment for the decryption key. The entire remediation process was costly and disruptive. This is the kind of scenario that plays out repeatedly in 2025 and 2026.

Large enterprises are not immune. When endpoints lose their defenses, whole fleets of devices can be infected, leading to business interruption, loss of sensitive data, and long hours of recovery work by malware incident response teams.

What Defenders Can Do Today

The first step is knowing the attack surface. If your team uses only the default Defender without layered controls, the risk is greater. Tools that monitor registry changes, script execution patterns, and unauthorized interactions with the Windows Security Center can help flag suspicious events before they cause lasting damage.

Training users about phishing and socially engineered files remains crucial, because many of these attacks start with a trick rather than a technical exploit. Behavioral monitoring and endpoint hardening strategies also help. This includes least‑privilege user policies, strict PowerShell execution policies, and blocking untrusted code execution.

Organizations may also consider investing in stronger endpoint protection service software that includes advanced heuristics, anomaly detection, and automatic rollback capabilities that can respond when Defender is disabled or compromised.

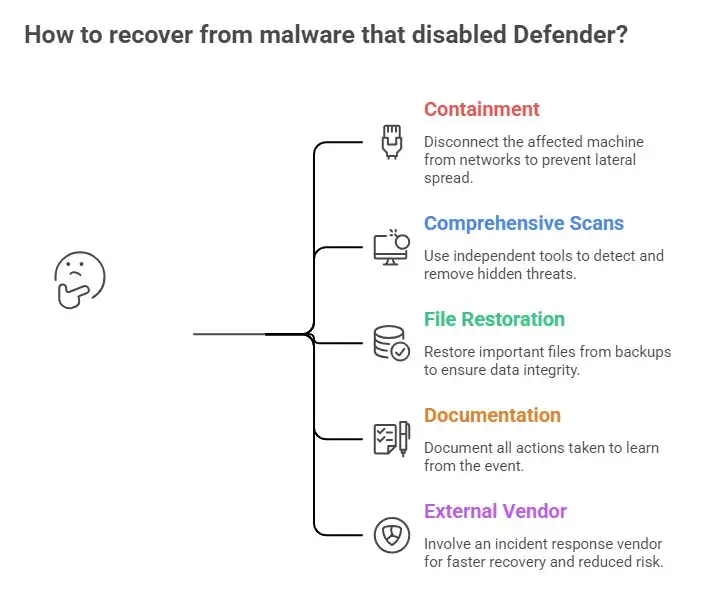

How to Recover If You Are Infected

If you suspect your system has been hit by malware that has turned off Defender, immediate action is important. The first priority is containment. Disconnect the affected machine from networks to prevent lateral spread.

After that, experienced responders recommend running comprehensive scans with tools that are independent of the compromised operating system. Bootable rescue environments or separate scanning appliances can help detect and remove hidden threats. This relates to questions like “How to remove malware that disables Defender in Windows,” which should always be addressed by professionals, especially in more serious cases.

Once removal steps are underway, restore important files from known good backups. Ensure you document all actions taken so your team learns from the event. For organizations, involving an external incident response vendor can speed recovery and reduce long‑term risk.

Practice Good Cyber Hygiene

There is no single magic bullet, but a combination of technology, policy, and awareness goes a long way. Updating systems regularly, using strong authentication, and monitoring unusual behavior can all reduce risk. Asking questions like, "Can malware turn off Defender permanently without appropriate controls?" is an important part of risk planning. It is possible only in specific conditions, usually when attackers already have significant access or administrative rights.

Frequently Asked Questions

How to detect multi-stage Windows malware?

Detecting these threats typically requires monitoring at multiple levels, including script execution logs, registry changes, unexpected network connections, and unusual process creation. Tools with advanced behavioral detection are often necessary.

What tools prevent malware from bypassing Defender?

Strong Endpoint Detection and Response (EDR) products, modern Endpoint Protection Platforms (EPP), and supplemental third‑party security suites can offer layers beyond the built‑in Defender.

What are Windows Malware Neutralizing Defender best practices?

Keeping Defender and Windows fully updated, limiting administrative privileges, enforcing script execution policies, and using layered security are all recommended.

Hoplon Insight Box

Invest in layered defenses. Relying solely on built‑in antivirus like Defender is no longer sufficient against advanced threats that can disable it. Harden PowerShell execution policies. Monitor registry and security center API interactions. Conduct regular drills with your IT team to respond quickly to infection scenarios, focusing on Windows malware remediation and rapid malware incident response.

Trusted Source: Fortinet Labs analysis of multi‑stage Windows malware campaigns provides a detailed technical breakdown of how these threats bypass defenses and deploy payloads.

Share this :