Social Engineering Attacks: The Human Exploit in Cybersecurity

Hoplon InfoSec

18 Jun, 2025

Understanding Social Engineering

Definition and Scope

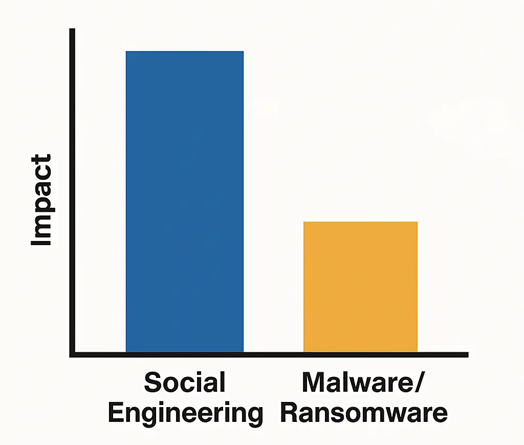

Social engineering is a form of cyberattack that relies on manipulating human psychology rather than exploiting technical vulnerabilities. It is a deceptive method where attackers trick individuals into revealing confidential information or performing actions that compromise security. These attacks often mimic legitimate communications or personas to gain trust and control, making them particularly dangerous and effective.

Unlike malware or ransomware, social engineering does not require advanced technical knowledge to initiate. Instead, it leverages the power of persuasion, deceit, and emotional manipulation to breach an organization’s security. The attack surface is wide and anyone with access to sensitive data can become a potential target, including employees, customers, and third-party vendors.

The Advantages of Social Engineering (For Attackers)

Low Technical Barriers

One of the reasons social engineering is so widely used among cybercriminals is its simplicity. Unlike sophisticated hacks that require knowledge of programming, network configurations, or software vulnerabilities, social engineering can be executed with little more than a convincing email or a persuasive phone call. This makes it accessible to a broader range of attackers, from lone individuals to organized cybercrime groups.

High Return on Investment

For malicious actors, social engineering presents an attractive return on investment. A single successful phishing email or impersonation attempt can lead to significant rewards, such as access to sensitive databases, financial accounts, or intellectual property. The relative ease and affordability of launching these attacks make them a popular choice among threat actors.

Difficulty in Detection

Social engineering is notoriously hard to detect using traditional cybersecurity tools. Firewalls, intrusion detection systems, and antivirus software are built to combat technical threats, not human decisions. Since social engineering often involves seemingly innocent communications like an email or a conversation, it can go unnoticed until the damage is done.

Bypassing Traditional Security Layers

Attackers use social engineering to bypass layers of defense that focus on system integrity. An organization may have complex authentication processes and encryption methods in place, but if an employee is tricked into handing over their credentials, those protections become irrelevant. This ability to circumvent standard protocols makes social engineering a formidable threat.

Customizable for Scale or Precision

Social engineering techniques can be adapted for various contexts. Mass phishing campaigns cast a wide net, targeting thousands of users with generic messages. On the other hand, spear phishing targets specific individuals, often high-ranking executives, with customized messages that appear highly legitimate. This versatility allows attackers to tailor their approach for maximum impact.

The Importance of Understanding Social Engineering

Human Error as a Cybersecurity Vulnerability

Despite advances in cybersecurity technology, human error remains the leading cause of data breaches. Social engineering exploits this vulnerability by encouraging individuals to act against security best practices. Whether it’s clicking a malicious link or revealing confidential data over the phone, a single mistake can expose entire systems to risk.

Impact on Organizational Security

Social engineering attacks can serve as the entry point for larger, more destructive breaches. By obtaining initial access through deception, attackers can plant malware, exfiltrate data, or even escalate privileges within the network. The initial deception may seem minor but can have far-reaching consequences for the organization’s integrity and continuity.

Evolution of Attack Tactics

As technology evolves, so too do social engineering techniques. Attackers now use AI tools to generate highly realistic fake emails, mimic voices in vishing attacks, or create deepfake videos to impersonate executives. This increasing sophistication makes traditional training and awareness efforts more crucial than ever.

Legal and Regulatory Repercussions

Organizations are under increasing pressure to secure data due to stringent data protection laws like GDPR, HIPAA, and Canada’s PIPEDA. A successful social engineering attack leading to a data breach can result not only in financial losses but also in legal penalties and regulatory investigations. These repercussions underscore the importance of preventive strategies.

Erosion of Trust and Reputation

Beyond tangible losses, a breach due to social engineering can severely damage an organization’s reputation. Clients, partners, and stakeholders may lose confidence in the organization’s ability to safeguard information. Restoring this trust can be far more difficult than addressing the immediate damage caused by the breach.

Key Features of Social Engineering Attacks

Psychological Manipulation

The cornerstone of social engineering is psychological manipulation. Attackers exploit basic human instincts and emotions to influence decisions. For example, urgency is a powerful motivator, an email warning of account suspension if a user doesn’t act quickly can push even cautious individuals to react without verifying the message.

Impersonation and Deception

Most social engineering attacks involve impersonation. Attackers may pose as company executives, IT support, government officials, or vendors. The effectiveness of the deception often depends on how much information the attacker has gathered beforehand, making pre-attack research a critical phase.

Use of Pretexting

Pretexting involves creating a fabricated scenario to gain access to information. An attacker might pretend to conduct a company survey or a compliance check, creating a pretext that appears both official and harmless. The target is drawn into the scenario and convinced to provide information or access.

Emotional Triggers

Social engineers often design their attacks to provoke specific emotional reactions, fear, greed, urgency, or curiosity. A message claiming that the user has won a prize, or one that warns of suspicious account activity, are common examples. These emotional triggers are used to lower the user’s defenses.

Minimal Use of Technical Tools

Many social engineering attacks do not rely on malware or hacking tools. A convincing email, a spoofed caller ID, or a forged document may be enough to deceive the target. This lack of technical indicators makes these attacks difficult to trace and prevent through traditional methods.

How Social Engineering Works

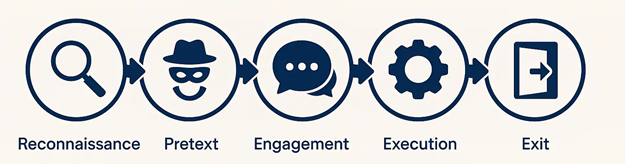

Stage 1: Reconnaissance

The first step in any social engineering attack is gathering information about the target. This may involve scanning social media profiles, corporate websites, or public directories to understand organizational structure, internal jargon, or upcoming events. The more information an attacker gathers, the more believable their impersonation becomes.

Stage 2: Establishing a Pretext

Once enough information is collected, the attacker creates a pretext, a believable scenario used to justify their request. For example, posing as a new employee needing urgent access to systems or pretending to be a vendor seeking payment clarification. The pretext sets the stage for the victim to comply without suspicion.

Stage 3: Engaging the Target

At this stage, the attacker contacts the target using the chosen method, email, phone, SMS, or in person. They use the pretext to build trust and manipulate the target into taking a specific action. This might include clicking a link, downloading an attachment, or providing login credentials.

Stage 4: Execution of the Attack

The manipulation culminates in the execution phase. The attacker may install malware via a downloaded file or gain access to systems using stolen credentials. Often, the attack continues to escalate from here either by moving laterally across the network or using the gained access to target others within the organization.

Stage 5: Covering Tracks

A skilled social engineer will take steps to minimize detection. This may include deleting email traces, using temporary communication channels, or using anonymous tools to mask their identity. The goal is to avoid detection for as long as possible, allowing further exploitation or data extraction.

Common Types of Social Engineering Attacks

Social engineering attacks come in various forms, depending on the communication medium and tactics used. While the core principle remains the same deceiving the victim, the method of execution differs.

Phishing

Phishing is the most widespread type of social engineering, typically executed via email. The attacker sends a message that appears to come from a trusted source, such as a bank, employer, or popular service. These messages often contain links to fake websites that capture login details or distribute malware.

Spear Phishing

Spear phishing is a more targeted version of phishing. Instead of a mass email, the attacker crafts a highly personalized message based on specific knowledge about the recipient. These attacks are harder to detect and often more successful because they mimic legitimate communication convincingly.

Vishing and Smishing

Voice phishing (vishing) and SMS phishing (smishing) use phone calls and text messages to deceive victims. A vishing call might impersonate a bank representative or IT support, while smishing might prompt users to click a link to claim a prize or secure their account.

Pretexting

Pretexting involves inventing a fake identity and scenario to gather information or gain access. This method is commonly used in corporate espionage or fraud, where the attacker might pose as a law enforcement officer or external auditor.

Baiting and Tailgating

Baiting involves offering something attractive like a free USB drive or software download, that contains malicious code. Tailgating refers to physically following authorized personnel into a restricted area without credentials, often by exploiting polite social behavior.

Defending Against Social Engineering

Security Awareness Training

The most effective defense against social engineering is a well-informed workforce. Employees should be trained to recognize the signs of manipulation and know how to respond to suspicious activity. Training should be frequent and updated to reflect the evolving nature of these threats.

Verification Processes

Implementing strict verification protocols can reduce the effectiveness of impersonation attacks. Employees should be instructed to confirm sensitive requests through alternate channels such as a phone call or face-to-face conversation before complying.

Multi-Factor Authentication

While social engineering often targets passwords, enabling multi-factor authentication (MFA) can serve as a barrier. Even if credentials are compromised, an additional authentication layer can prevent unauthorized access.

Incident Reporting and Response

Encouraging a culture of transparency and swift reporting is essential. If an employee suspects they’ve been targeted, quick reporting can mitigate damage. Organizations should have clear incident response procedures in place to deal with such threats.

Conclusion

Social engineering is a powerful, deceptive tactic that continues to challenge even the most secure organizations. By targeting human behavior rather than software flaws, it bypasses traditional defenses and exploits the trust and cooperation that underpin professional environments. As these attacks become more sophisticated, the responsibility to defend against them falls not just on IT departments but on every individual within an organization.

The key to minimizing risk lies in understanding the nature of social engineering, recognizing its warning signs, and cultivating a culture of vigilance and skepticism. In an age where information is both an asset and a weapon, awareness is the first and sometimes only line of defense

Did you find this article helpful? Follow us on Twitter and LinkedIn for more Cyber Security news and updates. Stay connected on Facebook and Instagram as well. At Hoplon Infosec, we’re committed to securing your digital world.

Share this :