Inside the Invisible Trade of Zero-Day Exploit Marketplaces:2025

Hoplon InfoSec

20 Sep, 2025

Zero-Day Exploit Marketplaces

Imagine a market where a single secret bug can fetch the price of a new house. It is not a market you shop in with a credit card. It is a place where silence has value, and secrecy is the product. Welcome to the shadowy economy of zero-day exploit marketplaces, a topic that sounds like a thriller but is very much real and worth understanding if you run systems, build software, or care about privacy.

This piece is not alarmism. It is a guide. I will walk you through how these markets work, who moves money, and what you and your team can do to reduce risk. Along the way I will use real examples, a few plain stories, and some blunt tradecraft so the subject loses its mystique and becomes manageable.

What are zero-day exploit marketplaces?

At its simplest, a zero-day is a software flaw that the vendor does not yet know about. An exploit is the practical method for using that flaw to break into or control a system. When these two things are packaged and sold, a market is born. Zero-day exploit marketplaces are the venues and networks where such trade takes place.

These places are not a single storefront. They range from private brokerages that sell to governments to forums on the dark web where less vetted buyers can trade payloads or exploit code. Some channels are highly curated and contractual. Others are chaotic and criminal.

A short history of the trade

The trade did not appear overnight. Early bug bounties and vulnerability-reward programs created a legal path for researchers to disclose flaws. At the same time, demand sprang up for exclusive, unreported flaws for intelligence and law enforcement uses. Over the last decade, markets evolved to include firms that aggregate exploits and sell them on subscription or on contract. This created professional middlemen who could match sellers and buyers while promising exclusivity and nondisclosure.

Those middlemen changed the economics. When governments, private firms, and criminal groups all wanted exclusives, prices rose, and entire businesses formed around acquisition, vetting, and resale. Academic work that studied these brokers shows they behave like market makers, handling negotiation, escrow, and quality assurance for exploits.

Who participates: sellers, buyers, and middlemen

On the seller side you find security researchers, freelance hackers, and sometimes insiders who discover bugs during normal work. Sellers make a decision: disclose responsibly and get a small public bounty, or sell into more lucrative private channels. Buyers range from national intelligence services to private surveillance firms and criminal gangs. Middlemen are firms or brokers who package exploits, test them, and market them to high-paying clients.

Understanding motives helps. Some sellers are financially motivated. Others sell for reputation, access, or even because they are coerced. Buyers do not all share the same intent. Some purchase exploits for defensive research and testing. Many do not. That ambiguity is the reason the trade attracts constant scrutiny.

How deals are structured and priced

Prices depend on target, complexity, and exclusivity. A remote code execution flaw in a widely used mobile app or operating system can command seven figures. Less critical bugs sell for thousands. Brokers will often demand exclusivity guarantees and provide contracts that limit resale. Evidence shows that as products hardened, prices jumped because good, working exploits became rarer and therefore more valuable. That shifting price dynamic is visible in public coverage of exploit acquisition firms and pricing lists.

Buyers pay a premium for zero-click or fully stealthy exploits because they allow access without user interaction. Selling chains may include staged payments, escrow, and demo proofs. Some transactions are one-off sales. Others are long-term subscriptions where a broker offers a rotating library of fresh exploits.

Where vulnerabilities come from

Vulnerabilities arise in many ways. Sometimes they are stumbled upon during routine research. Other times they come from complex reverse engineering, fuzzing campaigns, or targeted probes against a vendor. There are supply chains too. Third-party libraries, plugins, and poorly maintained components are fertile ground.

When a researcher finds a bug, they face choices. Responsible disclosure to the vendor can lead to a patch and a modest public reward. Selling into private markets often pays far more but removes the opportunity to fix the issue for everyone. That choice is at the moral heart of the whole market.

What buyers want and why demand keeps rising

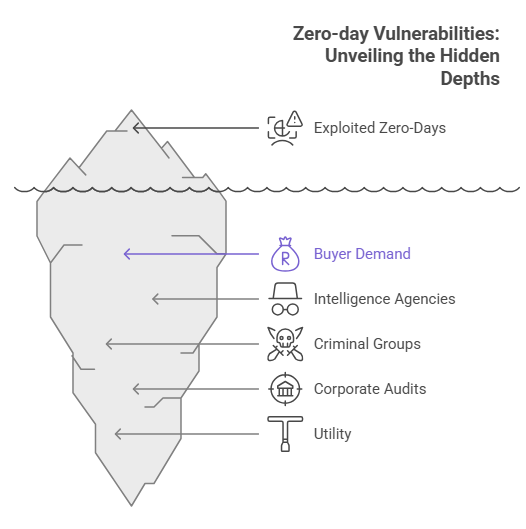

Buyers want exclusive access, stealth, and persistence. Intelligence agencies prize stable, reliable exploits for covert operations. Criminal groups want scalable, anonymous payloads to monetize at scale. Corporations sometimes want exploits to audit and test their defenses. The common thread is utility. A zero-day that reliably bypasses protections is a tool that can be used repeatedly until a patch arrives.

Several reports indicate the number of widely exploited zero-day vulnerabilities has increased in recent years, driven by both detection improvements and persistent demand. As defenders get better, buyers pay more for truly novel techniques, which in turn fuels the market.

The dark corners: forums, brokers, and secret auctions

Not every trade happens in polished contracts. Some deals take place in closed forums, invite-only chats, and encrypted marketplaces. Others are brokered through firms that maintain strict vetting and operate almost like private equity houses for exploits. The lowest layers of the market can feel like any other darknet trade: reputations, escrow, code reviews, and the occasional scam. Analysts who studied the dark web found active listings for malware and exploit code, meaning the supply side is multi-tiered and resilient.

For defenders the danger is twofold. First, exploits can be reused and propagated quickly. Second, once an exploit is weaponized and distributed, patching and detection become a race against time. That is why even small organizations must assume they could be targeted by tools purchased far away.

The thin line between markets and mercenary services

The line between selling an exploit and selling someone access is thin. Some vendors provide the exploit as a service, embedding it into a tailored payload, offering installation support, and providing operational guidance. That turns a one-time sale into a longer service contract. Historically, leaks from surveillance vendors and spyware firms showed how professional this business can be and how clients can abuse it. Those incidents forced public debates about accountability and oversight.

Famous incidents and wake-up calls

Leaks and investigative reporting have exposed how exploits sold through private channels were used against journalists, activists, and foreign officials. Examples from high-profile spyware and vendor leaks provided vivid evidence that these markets are not hypothetical threats. These public revelations have prompted lawsuits, regulatory scrutiny, and policy debates.

When such events hit the headlines, they force vendors to act, but they also show how quickly a discovered exploit can be weaponized when it enters the wrong hands. For defenders the takeaway is simple: assume tools exist that could bypass traditional protections and plan accordingly.

Ethical, legal, and reputational risks

Selling or buying exploits carries real-world consequences. Firms that act as brokers may face reputational damage if their customers misuse tools. Sellers who provide vulnerabilities to questionable buyers risk legal exposure in some jurisdictions. And governments that stockpile zero-days face a tradeoff between national security uses and the broader public good of an internet that is more secure for everyone.

This is not purely theoretical. Courts, regulators, and civil society groups have started to push back when surveillance tools are abused. Lawsuits and rulings are changing what some vendors can do and whom they can sell to.

How defenders and vendors see the market

From a defender perspective the market is a major source of uncertainty. Vendors must patch fast, improve telemetry, and assume that many exploits are not disclosed before being used. Industry reports and telemetry from major security teams show steady waves of targeted exploitation that often trace back to purchased exploits or mercenary services. That data has pushed defenders to emphasize layered controls, detection engineering, and rapid patch programs.

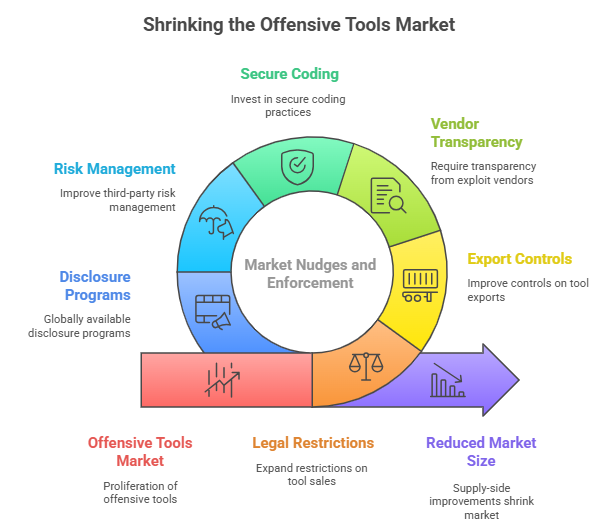

Vendors are also experimenting with more aggressive disclosure programs and expanded bug bounties to disincentivize selling to private buyers. The logic is straightforward: pay researchers reasonably, and you can lower the supply that might otherwise feed darker markets.

Practical steps organizations can take right now

You do not need a year of security budget to reduce exposure. First, get your patch management under control and track high-value assets. Second, assume compromise and invest in detection engineering so an exploit does not give unfettered control. Third, harden identity and segmentation so a breach is costly to the attacker.

On the people side, ensure communication channels with vendors are clear. If you suspect you were targeted with a sophisticated exploit, work with incident response teams who have experience handling advanced threats. Those teams know how to preserve evidence and coordinate with vendors and authorities.

Policy, regulation, and possible fixes

Fixing the problem requires both market nudges and enforcement. Expanding legal restrictions on the sale of offensive tools, improving export controls, and requiring more transparency for vendors who broker exploits can help. At the same time, broader investments in secure coding, third-party risk management, and globally available disclosure programs will shrink the market through supply-side improvements.

Policymakers are debating where to draw the lines between legitimate research, defensive use, and offensive capability. The case law and regulatory landscape are still developing, and the choices made now will shape the next decade of how these markets operate.

A cautious look ahead and closing takeaway

Zero-Day Exploit Marketplaces are not going away. They are a market response to supply, demand, and the incentives in the system. But visibility, better disclosure practices, and smarter procurement choices can make the internet safer without pretending the problem can be solved overnight.

If you take one thing from this, let it be practical. Treat the existence of these markets as a risk vector, not as a mystery. Invest in patching, detection, and supplier diligence. Build processes that assume adversaries may already have advanced tools, and you will make those tools less useful.

Follow us on X (Twitter) and LinkedIn for more cybersecurity news and updates. Stay connected on YouTube, Facebook, and Instagram as well. At Hoplon Infosec, we’re committed to securing your digital world. Hoplon Infosec’s Deep and Dark Web Monitoring service helps organizations spot exploit activity, leaks, and emerging threats in hidden marketplaces, giving you the visibility needed to act before attackers do.

Share this :