Security News Recap: Zero-Days & Patch Updates

Hoplon InfoSec

13 Feb, 2026

Over the past week, several stories have surfaced that look unrelated on the surface: Windows 11 cumulative updates, a reported Windows remote-access service denial-of-service issue, a phishing wave abusing Signal device linking, Apple Pay-themed phishing lures, a Windows screensaver malware trick that installs legitimate remote management tools, a SolarWinds Web Help Desk compromise pattern that leaned on DFIR tooling, and a WormGPT data leak claim that has the security community arguing about trust in criminal AI services.

What ties them together is not the brand names. It’s the operational lesson: modern incidents often succeed by blending into normal behavior, normal tooling, and normal routines. Attackers increasingly win by looking “legitimate” long enough to get a foothold.

In this guide-style weekly recap, you’ll learn how these attack patterns work, what they mean for real environments, and how to build a repeatable response playbook that keeps your team calm and effective.

What Happened

This week’s security picture had five practical themes.

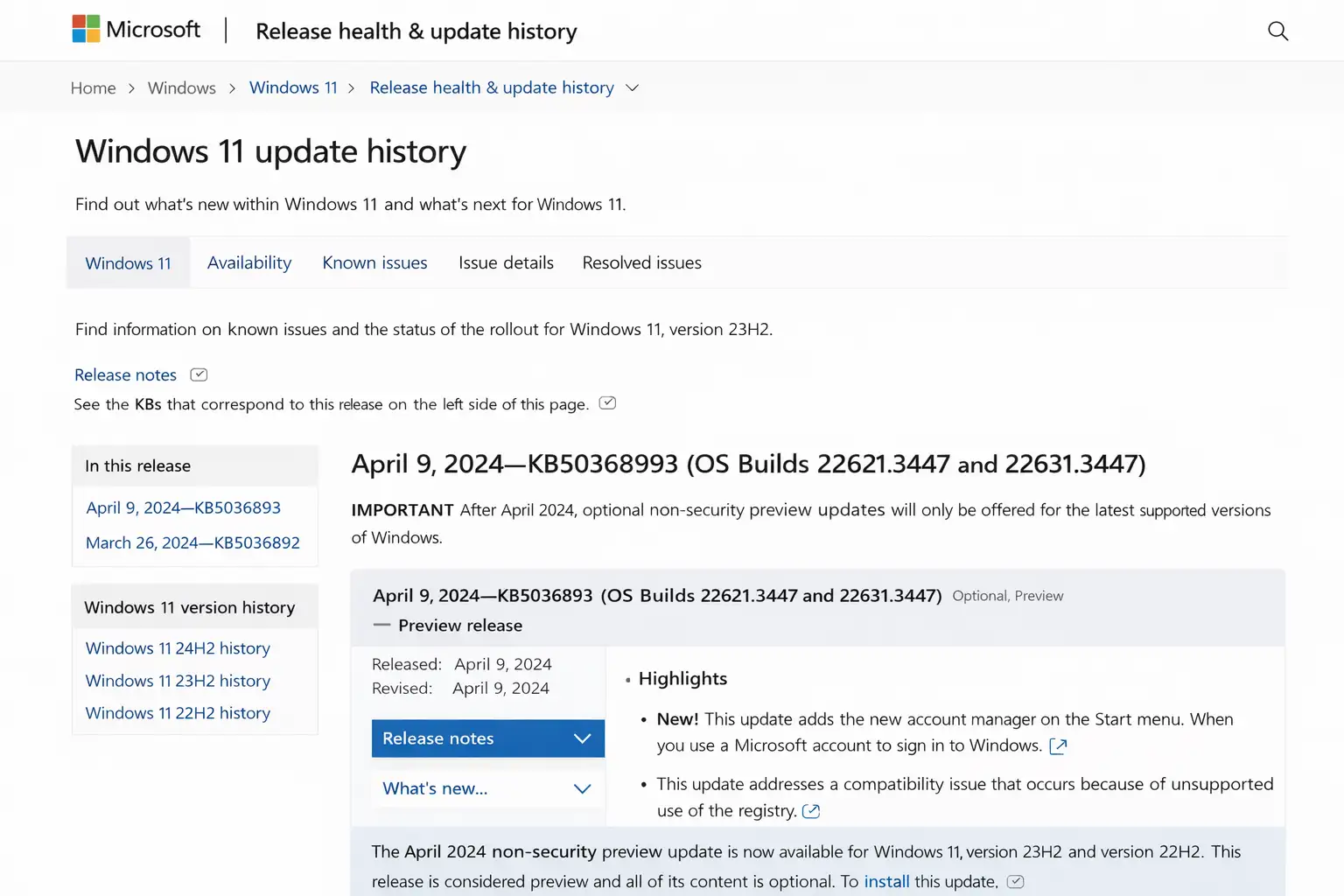

First, patching reality showed up again. Windows 11 cumulative updates matter because they roll many fixes together and reduce version drift across fleets, but only if they are deployed quickly and safely.

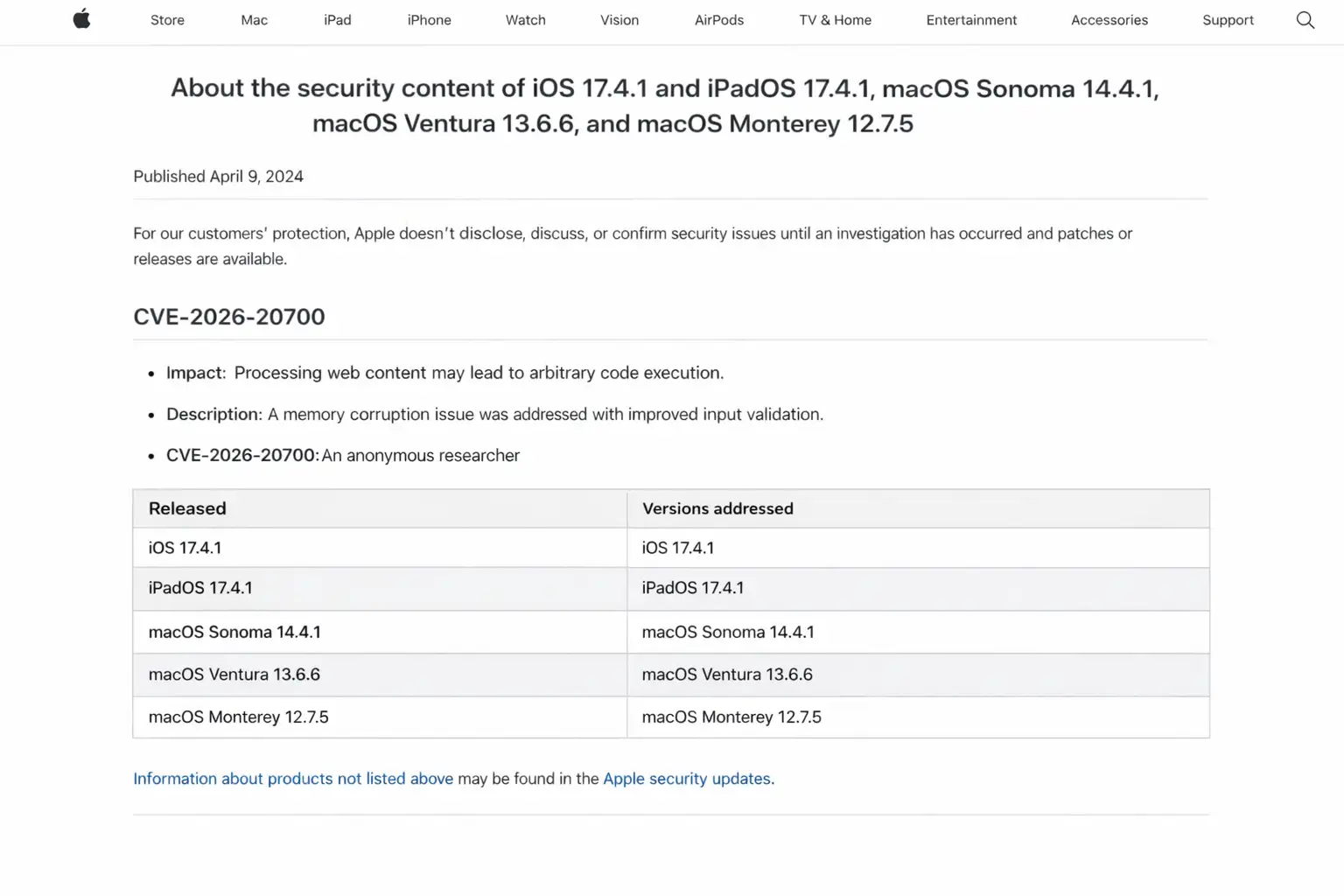

Second, zero-day urgency hit Apple users. Apple patched an actively exploited issue, CVE-2026-20700, described as a memory corruption problem in dyld (Dynamic Link Editor). Reports credited Google’s Threat Analysis Group with discovery, and Apple said it may have been used in “extremely sophisticated” attacks against specific targets.

Third, remote access availability risk surfaced in Windows. Hoplon reported a Windows Remote Access Connection Manager (RAS) issue framed as a denial-of-service problem that can crash the service and disrupt VPN connectivity. At the time of writing, public reporting in that post does not clearly anchor the issue to a specific CVE, so treat details as “reported behavior” until a vendor advisory or CVE record confirms it.

Fourth, phishing evolved into workflow hijacking. German agencies reportedly investigated phishing that abuses Signal’s device linking flow to take over accounts without exploiting Signal itself. Separately, Apple Pay-themed phishing used fake alerts to push victims into credential entry and payment-related compromise paths.

Fifth, trusted tooling abuse kept popping up. A Windows screensaver (.scr) can run code like any executable and may be used to install legitimate remote monitoring and management (RMM) tooling for persistence. The SolarWinds Web Help Desk exposure story also described attackers installing DFIR tools to blend in rather than dropping obvious malware.

Why It Matters

A useful weekly recap should answer a blunt question: “Why do I care if I’m running a busy IT or security program?”

You care because these stories map to three high-cost outcomes: identity compromise, operational downtime, and stealthy persistence.

Apple zero-days are not “Apple drama.” Phones and Macs often act as identity hubs holding SSO sessions, MFA prompts, password manager access, and corporate email. A targeted compromise can become an identity incident even if the attacker never touches your laptop fleet.

Windows patch cycles are not “patch Tuesday trivia.” They are where entire exploit chains start or end. Cumulative updates fix classes of issues that attackers actively study, and delaying them expands the time window where your environment is predictable and vulnerable.

Phishing that abuses trusted workflows is not “just user error.” It’s an attack strategy that scales because it targets the lowest-friction path: getting a person to approve something that looks routine. If your security program treats phishing as only “bad links,” you’ll miss the bigger pattern: attackers are learning the UI of your tools and weaponizing it.

And finally, abuse of legitimate tools is not a niche IR story anymore. When attackers can use DFIR or RMM tooling, traditional detection that focuses on “known malware” gets weaker. Your best defense becomes context: who installed the tool, when, from where, and whether behavior matches your normal administrative patterns.

How the Issue Works

1) Windows 11 cumulative updates and why they change risk quickly

A Windows 11 cumulative update is a monthly package that includes previous fixes plus new security patches. That sounds boring until you realize what it changes operationally: it reduces patch fragmentation, which reduces “unknown pockets” of exposure across a fleet.

In older patch models, machines could miss different subsets of fixes. Attackers love that because it creates predictable weak targets. With cumulative updates, “latest” usually means “covered,” but only if your deployment is timely and consistent.

Microsoft’s Patch Tuesday cadence also shapes attacker timing. Researchers and threat actors watch patch releases closely. Even when exploit code isn’t immediately public, patch notes and diffing can reveal what changed, and that can help an attacker build a working exploit faster than many orgs can patch.

What this means in practice: your patch management is not an IT hygiene task. It is an exposure control system.

2) Apple zero-days: exploit chains, dyld, and why “targeted” still matters to everyone

Apple described this week’s actively exploited vulnerability as CVE-2026-20700, a memory corruption issue in dyld. In plain terms, dyld helps load and link programs, and memory corruption flaws can sometimes be leveraged to run attacker-controlled code in ways the system did not intend.

Modern Apple exploitation often involves an exploit chain. You might start with an entry point (web content, message preview, file parsing), gain initial code execution, then escape sandbox boundaries, then elevate privileges. “Zero-day” is about timing, not automatically about severity, but when Apple uses language like “extremely sophisticated,” it usually signals real-world exploitation, not a lab proof-of-concept.

Even if you are not a high-risk individual, the enterprise risk remains: one compromised device can become a credential and token problem.

3) Remote access denial-of-service: why availability attacks are still security incidents

Hoplon’s write-up frames a Windows Remote Access Connection Manager issue as a DoS risk: crafted traffic can crash the service and disrupt VPN users. The post discusses improper input validation and malformed negotiation packets triggering service failure.

Availability is not a second-class citizen in security. In a hybrid environment, VPN disruption can halt business operations, block admin access, and create messy secondary risk, like rushed workarounds that weaken controls.

Important accuracy note: If an issue is discussed as “0-day” but no CVE or vendor bulletin is clearly referenced, treat it cautiously. This appears to be unverified or misleading information, and no official sources confirm its authenticity.

If a Microsoft advisory or CVE emerges later, you can upgrade the confidence level and update your response plan accordingly.

4) Signal device linking phishing: hijacking a security feature without breaking encryption

The Signal phishing story is a good reminder that strong encryption does not prevent account takeover if the attacker can trick a user into linking a malicious device.

Signal supports linking additional devices. The reported phishing approach aims to get a victim to approve a linking request or share a one-time code. No software exploit required. It’s pure social engineering with a workflow twist.

If an attacker links their device, they can receive messages and silently monitor ongoing conversations. That’s devastating in government, journalism, and corporate environments where trust and confidentiality are essential.

5) Apple Pay phishing and fake alerts: making fraud feel like customer support

Apple Pay phishing often relies on believable urgency: “suspicious activity,” “your account is locked,” “verify now.” The lure pushes victims to click links, enter Apple ID credentials, or provide payment details.

Technically, it’s not “hacking Apple Pay.” It’s impersonating an Apple-like support experience and rerouting the victim to attacker-controlled infrastructure. The hard part is not building the phishing page. The hard part is making it feel routine.

6) Screensaver malware and RMM persistence: the old file type that still runs like an EXE

Screensaver files use the .scr extension. Despite the cozy name, they are executable programs. If a user runs one, it runs with the same permissions as other apps. Attackers can hide code inside a screensaver and then install legitimate RMM tooling for ongoing remote access.

This is the same strategic pattern as “living off the land.” Use what defenders already trust.

7) SolarWinds Web Help Desk exposure: quiet access, DFIR tools, and how attackers blend in

The SolarWinds Web Help Desk story described exploitation of exposed systems and a post-compromise phase where attackers installed DFIR tools instead of obvious malware. The goal was quiet observation, learning the environment, and staying undetected longer.

That detail matters because it flips many teams’ mental model. People often expect attackers to “drop malware.” In many modern intrusions, attackers drop tooling that looks like what your IT team already uses.

8) WormGPT breach claims: even criminals have supply chain problems

Reports this week claimed WormGPT user data may have been leaked, exposing emails and payment-related metadata for thousands of users, though confirmation from operators may be limited.

From a defender’s perspective, the more useful lesson is not the drama. It’s the trend: criminal ecosystems are messy, and data spills inside those ecosystems can create downstream harm, including extortion, doxxing, and copycat tooling.

A Realistic Attack Scenario

Here’s a scenario that feels uncomfortably plausible.

A mid-sized company runs hybrid work. They patch Windows monthly, but they do it in waves, and remote users sometimes delay reboots. Meanwhile, a few executives are heavy iPhone users and travel frequently.

On Monday, an attacker sends a Signal message to a staff member in finance pretending to be internal IT: “We detected unusual login attempts, please re-link your Signal device to secure your account.” The message includes instructions that sound like routine support.

The user approves a linking request. Now the attacker sees internal discussions about an upcoming vendor payment. They follow up with Apple Pay themed phishing to the same user, knowing they are likely to respond to “account security” prompts.

In parallel, a remote worker downloads what looks like a harmless “company-branded screensaver” from a shared folder. It is a .scr file that installs unauthorized RMM tooling. IT sees “remote management traffic” and assumes it’s normal, because the company already uses RMM for support.

None of this required a flashy exploit chain. It required routine behavior and blurred lines between legitimate workflows and attacker workflows.

That’s the uncomfortable truth a good weekly recap should surface.

Impact Analysis

Who is affected most?

This week’s themes disproportionately affect:

Enterprises with large Windows fleets and uneven patch deployment cadence

Organizations dependent on VPN and remote access, where availability hits become business outages

High-trust communications users (government, journalists, executives) who rely on Signal for sensitive work

Apple-heavy leadership teams, where one device compromise can become an identity compromise

Teams that use DFIR or RMM tools, because attackers can hide inside familiar tooling patterns

Threat Surface Heatmap

High risk this week

Identity hubs on mobile devices (Apple zero-day exploitation window)

Human-in-the-loop approval flows (Signal linking, Apple Pay alerts)

Medium risk this week

Internet-exposed IT management tools (SolarWinds WHD exposure patterns)

Unauthorized remote tooling persistence (screensaver → RMM)

Variable risk (depends on your environment)

Remote access service disruptions (reported Windows RAS DoS behavior)

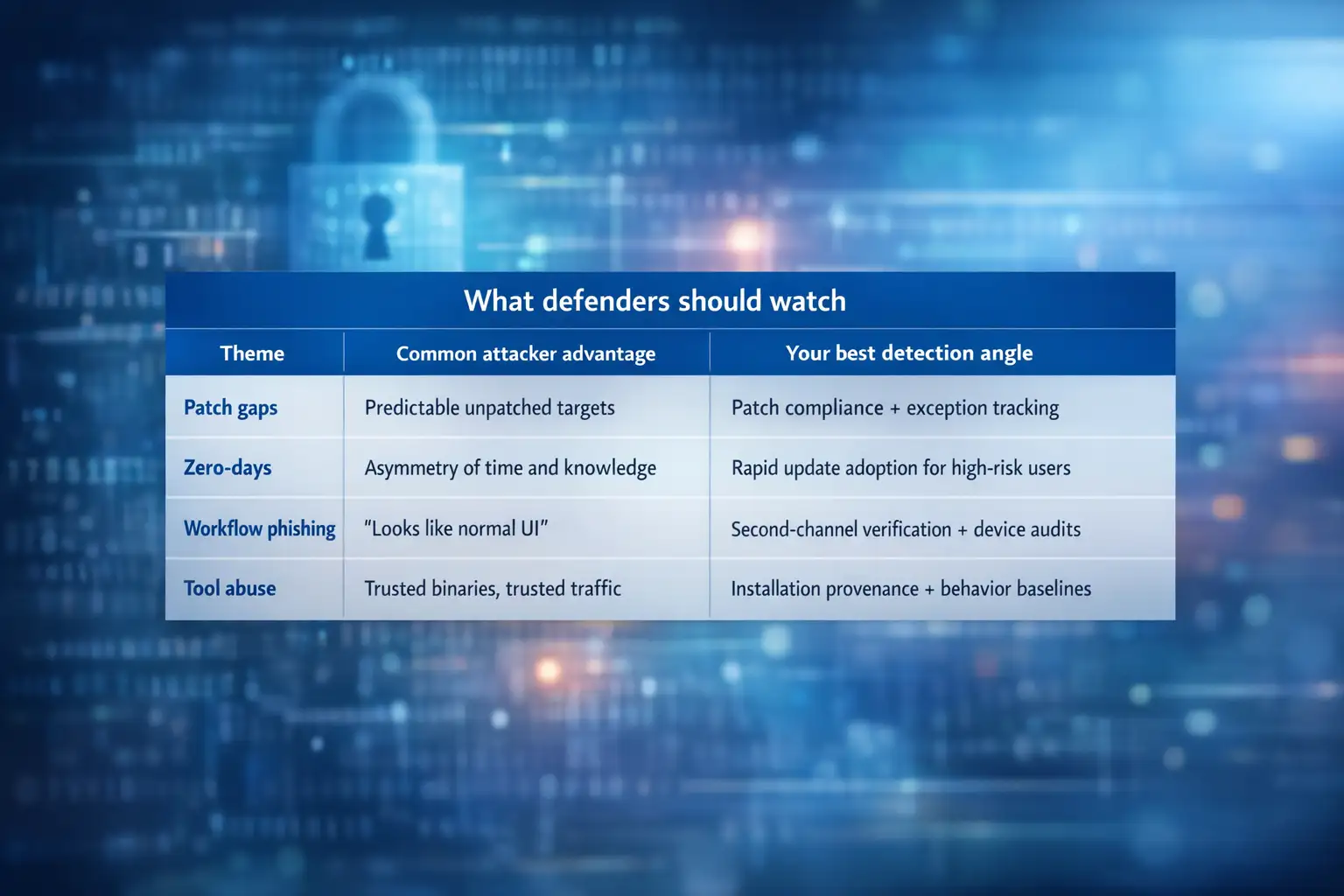

What defenders should watch

What Users or Organizations Should Do Now (Mitigation Steps)

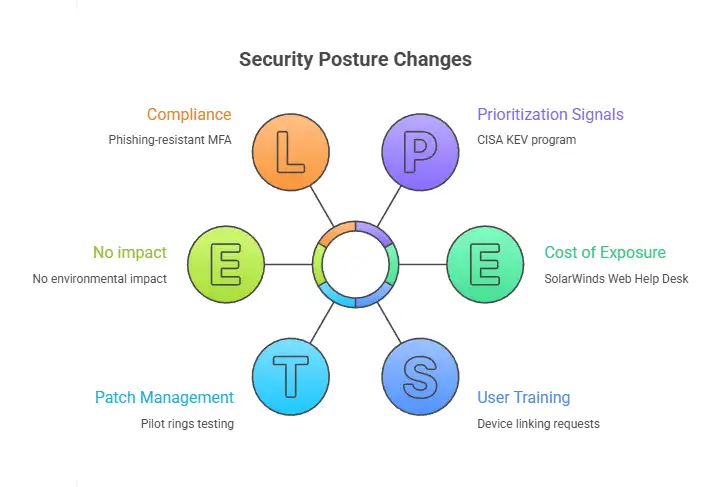

1) Patch with intent, not with hope

If you manage Windows 11, treat cumulative updates as security posture changes, not background maintenance.

Practical steps:

Pilot rings: test on a small ring, then expand quickly if stable.

Measure reboot completion: “installed” is not the same as “effective.”

Prioritize exposed endpoints: remote users, internet-facing services, and privileged workstations first.

For Apple fleets, move quickly when Apple confirms exploitation, especially for execs and staff with access to sensitive systems.

2) Treat linking, MFA, and approvals like privileged actions

For Signal:

Train staff that device linking requests are security-sensitive.

Encourage verification through a second channel (call, known internal chat, in-person).

Have high-risk users review linked devices weekly.

For Apple Pay themed phishing:

Teach users: real security alerts rarely demand immediate credential entry via a link.

Use conditional access and phishing-resistant MFA where possible.

3) Kill the “harmless file type” myth

Block or restrict unusual executable formats where you can, including .scr in email and web download contexts, and monitor for it in file shares.

Operational checks:

Alert on new RMM tool installs outside IT-approved software distribution.

Audit persistence mechanisms like scheduled tasks and registry run keys when suspicious tooling appears.

4) Reduce attack surface: internet exposure is still the easiest win

The SolarWinds Web Help Desk story reinforces a boring truth: management tools should not be public-facing unless absolutely necessary, and if they must be, they need layered controls.

Do now:

Inventory internet-facing services.

Close unnecessary exposure.

Add network restrictions, VPN, or zero trust access controls for admin platforms.

5) Use authoritative prioritization signals

If you need a neutral way to justify patch urgency, use CISA’s Known Exploited Vulnerabilities (KEV) program as a prioritization input for what to remediate first.

Broader Security Lessons and Future Implications

A good weekly recap should leave readers with durable lessons, not temporary anxiety.

Lesson one: attackers are blending in on purpose. DFIR tools, RMM tools, trusted workflows, and routine prompts are becoming attacker playgrounds because they reduce detection.

Lesson two: “targeted” today can be “scaled” tomorrow. Apple zero-days often start targeted, but the strategic insight spreads fast. Even if you are not the initial target, patching quickly keeps you from becoming the easy second-wave victim.

Lesson three: availability is security. A DoS against a remote access service can become a business continuity issue, which becomes a security issue when teams start bypassing controls to keep work moving.

Lesson four: criminals are not stable operators. The WormGPT leak claims, whether fully confirmed or not, point to a recurring reality: criminal services have operational security problems too, and those failures can spill into wider harm.

Common Misconceptions

Misconception 1: “If it’s encrypted, phishing can’t touch it.”

Encryption protects message content in transit. It does not protect you from approving a malicious device link or handing over a one-time code.

Misconception 2: “Cumulative updates are mostly bug fixes.”

They routinely close real attack paths. Delayed patching is not neutral. It’s exposure.

Misconception 3: “If the tool is legitimate, it can’t be part of an intrusion.”

Legitimate tools are often the stealthiest intrusion tools because they blend into normal admin activity.

Misconception 4: “A DoS is just an IT problem.”

Availability impacts can cascade into security exceptions, rushed workarounds, and loss of monitoring visibility. That’s a security problem.

Misconception 5: “WormGPT drama is irrelevant to defenders.”

The deeper point is about ecosystem risk: criminal tooling, AI misuse, and leakage can fuel future campaigns and extortion patterns.

Hoplon Insight Box

If I had to reduce this entire week into a tight set of priorities, it would be these:

Patch fast where exploitation is confirmed, especially Apple CVE-2026-20700 and any Windows fixes your environment depends on.

Train users on “approval phishing” where the attacker wants a link, a code, or a device pairing, not a malware download.

Treat new remote tooling installs as an incident until proven otherwise. Legitimate RMM does not mean authorized RMM.

Audit internet exposure of internal platforms. Most stealth intrusions start with something that should not have been reachable.

Write your internal weekly recap as a learning tool: what changed, what it means for you, what to do next Monday.

Conclusion

The most useful weekly recap is the one that changes behavior. This week’s stories were not random. They were a reminder that modern incidents often succeed by hiding inside normal routines: patch delays, approval flows, trusted tooling, and small convenience decisions that slowly become permanent.

If you patch quickly when exploitation is confirmed, lock down device linking and approval processes, and treat unexpected remote tooling as a real incident signal, you reduce risk in a way that holds up even when next week’s headlines look totally different.

That’s the point of a weekly recap that security teams can actually use.

FAQs

1) What is a weekly recap in cybersecurity?

A weekly recap in cybersecurity is a structured, educational summary that connects incidents to practical risk, explains how attacks work, and lists actions teams should take next.

2) How do I prioritize what to patch first?

Start with issues confirmed exploited in the wild and systems that are internet-facing or identity-critical. CISA’s KEV catalog is a reliable prioritization input.

3) What is “approval phishing”?

Approval phishing is when attackers try to get a user to approve something that looks routine, like a device link, MFA prompt, or security verification step, instead of delivering malware.

4) Can a screensaver really be malware?

Yes. A .scr file is an executable program. If it runs, it can install tools or payloads like any other executable, including legitimate RMM tools used for persistence.

5) Does the Signal phishing mean Signal is insecure?

Not necessarily. The reported abuse targets human decisions around device linking, not encryption. It’s a reminder that secure tools still depend on safe workflows.

6) What is CVE-2026-20700?

CVE-2026-20700 is an Apple zero-day described as a memory corruption issue in dyld, patched across multiple Apple platforms, and reported as exploited in sophisticated targeted attacks.

Share this :